![Stations [Excerpt]](https://miserytourism.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/stations-1024x657.png)

Stations [Excerpt]

EXCERPT from:

EXCERPT from:

Stations

Or,

The Mortification of the Reverend Holiday

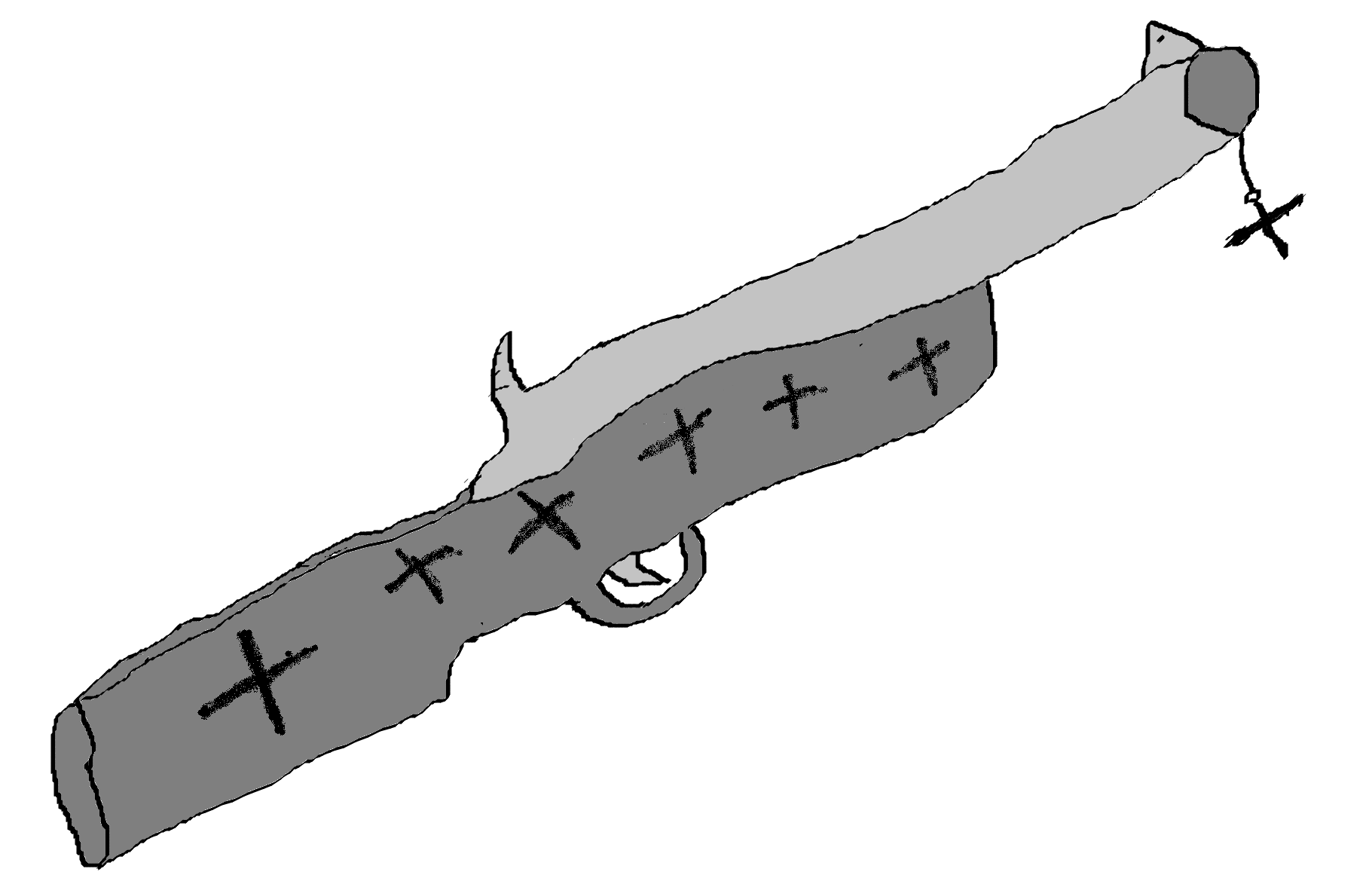

A little .22 snub-nose rat-gun isn’t ever going to do enough.

It’s been fired and will be again.

It’s made ruin of him, and the Doctor is saying he’s either lucky or stupid.

Margaret nods, though whether she’s heard is difficult to discern. She shifts her weight, one foot to the other, eye-to-eye with the Doctor outside her husband’s room, and another lump falls.

Last word before Clive’s final silence had her hammering down—the few books he had flying off the shelves, clothes thrown about in conflagrant fury, his broken-stringed guitar hurled cracking against the wall where it bounced and sang a tuneless moan, and she was gone then into the rising night—: that it was over.

But, it will be good!

It is now all tears for a not-yet-dead dying man—whose dying will be much longer in span, and death more pathetic, than any could yet know—and wiping away the evidence of the last living thing she’d allowed inside. Smeared and curdled out of its milk, near-iridescent flakes on her thighs. There’s still the taste of Clive in her mouth. Salty and thick like the tears that swell when she finds Dan all spewing gurgle and gout, a bleeding seizure on the living room floor, gun thrown a length away.

“Danny! Danny!” She cries, falling to her knees, the mess spreading cool on her seat as the blood warms against her legs. The room smells first of copper, then there’s all the other fearful odors—the muck-sweet soilings and stinging urine, nauseating piquancy as geysers from Dan’s mouth add half-digested clot to the purpling blood pooling all around.

Margaret’s tears keep her face clean…

That the man will die on his own is a forgone conclusion. Why he must die is another thing altogether.

He seems to have no problem looking Clive in the eye.

Margaret must wonder now if he’d known:

The two had met at a sacred place. Both at a zenith, both at a nadir, as is often enough near always the case. Dan still a Vicar and Margaret still a Maggie. Diminutives of what they’d one day become, uncurled sprouts in posture and spirit.

“Look,” the Pastor’d said, “you done perfectly good, Dan. Really.” And rose then to pull up his britches, sinch them tighter over the orb of his belly.

Vicar Dan nodded, the sermon’s manuscript crinkled and palm-stained in his hands.

“We all learn this lesson, and we all learn it the same way.” The Pastor rose, squeezed between his bookcase and desk edge, stomach nearly knocking over the lamp. Passed the defeated hunch of Dan without putting his broad hand on his shoulder. He peered a moment through the little cross-wire reinforced window. “All gone to narthex now. We’d better join, my son.”

The point had been made clear—To properly perform one’s pastoral position, all the beautiful exigencies of exegetic scholarship must be put by the wayside. Present the cleanest Gospel possible, in line not only with denomination and demands of the Synod, but also with the expectations of the congregation. This one, for instance, which early on in Dan’s vicarage the Pastor had described with no small festering boil’s ire as “Good liberal folks in a big liberal city struggling every day, each the one, with all this asphalt’s absence of the very goodness they feel their faith ought to vouchsafe them…” The Gospel they’d grown used to and come to expect was one of that easy, open-gated Heaven wherein all would be lily-white and the world below or behind or wherever whathaveyou was never of any consequence or reason at all to begin with. Ought to have been no surprise to precious, sweat-browed, mumbling Vicar Dan that they didn’t take to applause and shout and praise at his first sermon’s concern with the spiritual currency of suffering.

In the narthex, then. Donuts and plastic plates. Styrofoam coffees and handshakes. All the faces falling flat upon Dan, averting eyes once the contact had been made.

He blushed and sweat bloomed back as he poured himself a watery, thin brew from the urn. Nearly spilled it his shame shook him so bad, but she apologized loud, and it was true that she’s shaking too: “Oh no! I’m so, so sorry!”

Dan waved it away. Set the cup down, and searched out a napkin for his cuff. The woman found one faster and quick his hand was in hers.

She was young and smelled like cigarettes and kept saying sorry. Then she said, “I really liked your sermon…” And then that her name was Maggie. And then that she was new. And then that that wasn’t exactly true. That she had been to the narthex before a whole bunch because she attended a night meeting there once, sometimes twice, a week and had been attending for quite a long time. And that she didn’t know why she came, but she did and she was glad she did.

And he really shouldn’t’ve done what he did, but he did, and he listened to them speak:

“…and sometimes, I don’t know, sometimes I miss being meat. Just being meat. Sure, we always talk about this, that maybe it’s better in some way to put our feet down and, like, I don’t know, stick up for ourselves and our comfort and,” from a thin man, t-shirt and wringing hands, “but at least when I would just let these other guys do whatever to me I feel like I knew at least that I was the one letting them, that I could, theoretically of course, but theoretically I could always pull that away, that they could treat me like meat and then, if I got sick of it I could say, I could just say No! and then, like theoretically that would put a stop to it but,” and a face on his face like he’s listening to himself and knowing that none of this is close enough to true to believe; a lip-bit pause and breath and quiver in his cheeks, “I just, I know the problem is there’s no way to account for the thoughts of these other people and maybe if they’re willing to treat me like meat then they’re less likely to hear me and care if, I don’t know, if I were ever to try and say No! that it probably wouldn’t matter because like we always have to say that people only know us as we allow them to treat us and we’ll only ever see ourselves as we’ve allowed ourselves to be treated…”

And:

“…yeah, I shouldn’t have allowed myself to get that close yet,” flattened and dead-eyed, no faith in her speech; she ran her hand over her buzzed head and picked at a fresh tattoo on her wrist, “but, that’s always been my problem, you all know that by now. It’s always someone soft, too. That’s what I always feel the worst about, that it’s always someone who’s genuinely kind and nice, you know? And I just, I guess there’s something in me that likes when they,” and she made fists with her hands, nails in her palms until tendons screamed white beneath her skin, “break. But then they’re broken. And they ask you to fix them. They’re all so sweet, too, before they break. Sweeter sometimes after they’re broken, like this poor guy and, fuck… now what? Now I’ve got to tell him? Tell him that I can’t do this anymore because it’s the same thing I always do and that if he keeps trying to hold onto me it’ll be my fault that his life will never be the same, that I’m going to ruin him just for the fun of it and there’s not yet anything I can do about that? Why? I mean, I, I can see where the pieces go back together, I could put it all back together if… But, I don’t want to. I guess I always just want to throw the pieces further and further away from each other until there’s nothing left of him other than the place he stood begging me to break him in the first place…”

And then she:

Telling her story again for all gathered. Looking him in the eye. But, she’d been good. Maggie’d little to confess. She’d said that she almost feels guilty standing to speak when she’s got nothing to say, and the greasy-haired guy leading the meeting told her that we are all here to support each other in triumph just as much as in failure. So, Maggie said that everything had been fine and that she’d gone to church the previous week, that she’d actually gone to this church here that they’re all meeting in the narthex of and that she might be thinking about believing in God or something again because the young Priest—she’d said Priest, which wasn’t right but still gave Dan a smile to hide—said some things that seemed pretty wise: “He told us about how suffering is good. But, that it’s not good to go and try to get it. It’s good like nature is good. That it will always be there, and if we don’t fuss with it too much—”

It will be good! Though it hardly seems so now:

Fish-white leg poking out the sheets, the rest of him pain-killer limp. Tubes down his throat and the warbling song of machines. Head a bloody wrap. The only utterance, a moronic gurgle.

The slug had certainly scrambled some things in his skull that one in their right mind would prefer unscrambled, but the Doctor’s saying that people have lived full lives with less intact.

The little popgun round broke through his hard pallet, made a wreck of his sinuses and optical nerves, and bounced brutal through gray matter before coming to rest. In his convulsions before she found him, the mushroomed clump of lead came dislodged. He’d managed to swallow it. Inhale it, moreover. They found it glimmering in his windpipe during the emergency en route tracheotomy. A mass of shattered bone, blood, mucus, and burnt tongue was blocking his airway.

The doctor shows her the bullet, rattling in an orange pill bottle.

Margaret’d been mourning that night. Tears blurring the road as she drove too swiftly back to the parsonage, trying to cover twenty-some-odd miles in enough to time to use to the weekly ladies’ Bible-study as reliable alibi.

How the other women had managed to avoid telling Pastor Dan his wife had been increasingly absent for some months then seems a miracle. But, the rumor mill runs everything to grist. Listen to the tale full through to end of its telling and by then it’s so much dust fit to choke lungs. The only truth of any use is what remains: That Dan’s no earnest godsend and is far from kept in His speed, no holier than thou and far from immune to the moth and rust which grace is meant to inoculate one’s soul against—that even he is victim and held in no special favor. The way it ought to be.

The theatrics of tenure were met at the first with warmth and aplomb, the young Reverend Daniel Holiday having replaced a bumbling drunk of a Pastor who’d lost all apropos dignity, heaping upon himself all the aged congregation’s opprobrium after an Easter sunrise service’s tremulous performance. Shaking through the should-be joyous resurrection communion, little plastic wine-shooters tipped and clattering to stain the chancel’s green carpet all bruisy after a stuttering, sweaty, and flatulent sermon. The poor man’s withdrawals were obvious and he soon, before that season’s epiphany, was made to abscond to a rehab facility in the state’s capital, never to return even if the treatment had taken. The young Holiday taking his place, bringing with him all the fire, brimstone, and clenched severity the flock had come to recognize as shepherding.

He spat and sputtered through his sermons in those days, but it was obviously sat upon passion’s throne. The Word delivered not with salvation’s joy but the sharp, flinty edge of Truth carving through fat and flesh, tendon and gut, and all the blood washed clean away from the souls he meant to reach. His small-town, firm-browed congregation initially took quick and held fast to his difficult screeds—until, of course, they themselves were brought into question, until his preaching shifted focus to assure them that their attendance was no guarantee toward the quality of their faith.

There toward the end of his first year on the pulpit, they welcomed the new rumors of the man’s wife and her supposed failings. Pastor Holiday’s verbal war against misers and pride, against good stock-wisdoms, was simple to swallow along with the new, vernal sprouting suppositions of the man’s wife’s character.

When Margaret would attend the weekly studies, once her appearance was far from guaranteed, her presence was hugged close, and words of compliment fell from wine-stained mouths with bitter and bitten ease:

“Well, don’t we look bright today?” The doorway in which the woman stood gave entrance to one of the many homes just outside the city limit that Dan’s sermons served to condemn as damnable before his God of humility.

“Thank you. It’s only the weather, makes each the one of us glow.” Stepping in then, “You’re looking radiant yourself.”

“Certainly must be more than this sudden inclemency that’s got your cheeks alight…” Bigger on the inside and all the hallways opening up in tremendous rooms, each a with a purpose and whole in it. Air-conditioning had the had the place freezing up and from down the way Margaret could hear the other church hens, clucking and clinking glasses, a frightening skittering hush at the shutting of the door and then, steps down the hall, the ruffle rising again. Outside it was one of those sudden mid-autumn scorchers, summer’s last thrown assault on pleasantness and peace before handing over the responsibility to cruel winter. And on the skin that showed through Maragaret’s dress, her arms and neck and legs to just barely the backs of her knees, the sweat cooled quick to salt and shiver rose prickling.

Back at the parsonage, all Dan’s books and the low-light and the Church paying for everything, nothing gets fixed. Just about everything is the same as it has been since the Synod built the foundation and planted all those trees—near a hundred-some years back, now. Holds the heat. Days like the one in question, the home is oven hot and Dan had walked around the house, book up to his nose, in a pair of loose, white briefs, a hunchy pale twig, dirty boll head.

“Look who could make it today, ladies!” The kitchen’s blasted white and chrome and the squealing laughs and Maragaret’s caught up in all their arms as the phone in her purse sets buzzing.

And she comes to find later, in the hot, wet dark of fallen night, in the stale, reluctant air of her sedan, the messages reading, and then showing, pleas for attention and insult-ridden apology. Clive seemed then to have not believed her—all the grief, bargaining, and rage listed then on her phone’s screen, each missive a muted rattle against keys, makeup tubes, and credit cards. The interruption hardly registered to the bluer haired ladies, struggling as they appeared with their thoughts alone to weave strands of meaning together with regards to the revelation that Mary Magdalene had, in face, been no whore at all:

“Well, that’s just never at all how I’d learned it growing up…” The first to speak after the selected readings, scant as they were, and the silent skimming of the study guide they’d all bought at the recommendation of Pastor Holiday. “Were you aware of this, Margaret? Does the Pastor ever bring these sorts of things up?”

The wine had visibly taken to her cheeks and her tongue was slow. Hand clutching her little purse, that phone kicking all the while. “Oh, yeah, he brings up all sorts of wild stuff about it…”

“I mean, I just thought,” from one of the plump others, “I just always assumed she was important because she was such a, well, you know, big sinner and—”

“Well, it does say here,” a spidery hand pointing to the study-guide’s page, “that she was possessed by demons and—”

“It also says that she was a woman of means… Which I guess just meant she was—”

And then all the laughing again. Their eyes as well.

But now, their gaze’s nailed to their feet:

The Reverend Holiday sitting in the front pew, wife’s hand in hand, while Vicar Tori with the stern, shaking grin reads from the sermon manuscript given her just before service. Dan’s blasted mouth all a drool and his breathing a rattling wrack. Wipes blood-fleck glimmer from his lips and nods.

The Church has been full four Sunday’s running now—Pentecost, the post-Easter slough toward the Ordinary, wherein the blasting summer will render Sabbaths true in their rest and the pews emptied save for the staid and regular in their faith, who worship with hate, finding no kind glitter in their Christ and feeling themselves free of His judgement, the young parishioners disappearing, resurrected in the blood and fall of Spring and satisfied in having nearly done their duty from Advent on, remembering Christmas and given Lent a shot and the Ash and dour flickering light of Good Friday, dry fronds still stuck in the carpet like thrashed chaff—, the grotesque circus of the Reverend, theatre of misfortune, keeping all eyes open, ears pique, and mouths awed aghast as though in hungry witness to a public execution of a universally reviled heretic. Though, a survey of the gathered will reveal a buried truth and shame: That the heads of many women congregants remain bowed all through service, hands fiddling in their laps as if to scratch the grime of their knowledge from out under their nails. They look not up toward the front pew to see now that Margaret’s head rests on her husband’s shoulder, a warmth touch before he rises to conduct the sacrament in phlegmy silence.

There’s now a murmur about, and has been since the shot, that perhaps what the ladies thought they knew couldn’t have been the case—Couldn’t being operative, of course, in that the abjection of the glass-eyed, drooling, and tomb-toothed visage of the thing’s conclusion makes it so that it must be an impossibility. The chittering and giggles and grinding of rumor mills cease, all quiet comes down to drown the possibility that they really ought to have done something:

“Well, I just can’t say how it was any of my business to begin with.” Hushed and hissed through the receiver.

From the other, who’d called in huffing dread: “I know, I understand, hon. But, still, I can’t shake there’s something we ought to have—”

“Inn’t none of our business, never was, and there’s no proof but—”

The hickey she’d tried her damnedest to hide. Sweaters the summer before. Wet and looking near to fainting as Dan preached. The makeup Margaret had piled caky on her neck run to paste about her clavicle and, though honest in its fade, there shined out the bruise rouged nibble-blotch.

She’d seen the marking herself first in the mirror: Heart blasting furious, morning after the Thursday before and she’s torn from the bed unslumbered. Hadn’t slept a goddamn wink and Dan next to her a snoring rock, morning come to glow on the shame and ache that’d kept her awake, differentiated solely by locus upon skin or soul. The shame was easy to hide, a hard swallow and straightening face, but the aches, their source, was unalterable and plain—the size of his hands over her breasts delineated in yellowing purple; left nipple a twisted, bitten chap; thumb-pressed soft blooms about her hips; and the hickey shifting with every choked back sob—all from Clive’s beating himself into her.

She’d said yes without him even asking.

But, they couldn’t possibly have known that, and that’s the story they’ve decided to stick to. That they couldn’t have possibly known any of it, if there was anything to know at all anyhow.

They ought to have spoke.

Let the man know they knew what they knew.

What other cause than revelation could there be for the ‘accident?’ And that’s what it’d been called—the ‘accident.’ Some inexplicable how or another a bullet, small as it was, had found it’s way into the dear Reverend’s skull while his wife was where they all know nobody knows where—certainly not the study-circle!—Heavens! Regional head of the Synod come down, little Tori Estevez in tow, introduction in place of a sermon:

“Regardless of the current events and cause for my presence here in this chapel, I’d like to first off say that it is a pleasure to be here among all of you,” and his smile under the hair plugs, tight and brown with splashed-on tanning solution. “I believe I see even now some new faces, so this introduction will be a joyous addition to what seems to me now to be a growing and vibrant congregation…”

He, or someone very like him, has previously been to visit. Annual little drop-ins, but the last time he needed to make an appearance at the pulpit was to introduce to them all their new shepherding Reverend, Daniel Holiday—a man who, by the words of this man or someone very like him, “…has proven himself not only truly dedicated among the faithful, but also a powerful advocate for continuing in our time the wonderous and charitable works that Christ commanded of us in his. All to say—”

Not so much unlike the praises poured to anoint the tenure of Vicar Estevez, who was, is, and proves herself every day to be, “…one of the Church’s top people, a splendid presence and generous soul, who will do all she can to make this transition easy and quell any anxieties about what has happened and what will come to happen in the weeks ahead.”

She came all a grin and tender hands, touching shoulders and rubbing arms. Hair cropped short, face all open so her eyes could shine, Tori’s got deep threatless laugh lines, skin like sunned from work, and the biggest teeth anyone’d remember seeing—she’s a beam when she says, “There’s never a way to know why things happen when we ourselves haven’t born witness to them.” A warm comfort breaking through clouds when, near to cooing, she insists, “And even were we to know the contents of another’s heart, would it be so much more enlightening?” A tear falls from the worried eye of elder lady, one of the few who thought they knew and never spoke, when Vicar Tori wraps her in viny embrace, a tender clamoring with respect toward the woman’s frail body and spirit, and whispers, “It’s better to look inward, now. And that is prayer, my dear. It’s better to pray and give it all up to God, who knows all there is to know and all there is not to know. Don’t think too much of the contents of the souls of others, accident or not what has happened has happened and must be forgiven, that is our commandment. So, forgive and pray that this will not always be the state of things…”

And that seems, on the surface, reason enough for the shot going off in the first place. A prayer of sorts, a quiet, muffled, sudden gesture against the state of things. Why Dan’s resoundingly and unanimously thought to have known, to have found out somehow.

The only explanation for it as it has come to be: that he’s driven to it by desperation and heartbreak and the weight of the lie—that man of strong faith as all have seen demonstrated time and time again in word and deed and word and word, who traffics heavy in the truth of that which is fundamentally unknowable, confronted by a formerly unknown truth which by way of its revelation, knowledge irrefutable and solid and provable by all sopping, screamed, and wet evidence, must be accepted as inextricable with reality, as reality itself, as the thing happening in the dark still occurs despite the lack of light to show it, dropped from his pulpit like an unfairly blasted dove from its olive branch, to twitch and bleed and try dying in the duff, only to be revived, revivified but silent and, now, blessed now—the grace itself and by grace alone!—now shaking the very man’s hand without tremor or sweat or break in their eyes.

Dan’s wrecked mouth makes as to smile. And his palm comes out of the grip rosy, squeezed by the dry paw of his counterpart near to break.

“Nice to meet you, father.” Clive says and looks back up over his shoulder to Margaret still standing in the doorway. “Sorry to hear about all that’s happened. I’m glad you seem to be recovering well.”

Margaret then at his side, saying, “Let me take those, Clive.” In reference to the box of supermarket brand cookies he’s brough to the parsonage as a gift. “I’ll put them in the kitchen.”

And Clive’s eyes rise to follow her travel through the living room, making a turn and disappearing.

Whether Dan’s eyes follow Clive’s is impossible to determine, as after the greeting he’s sat back in his reading chair, under the lamp, the ream of printer paper upon his lap again, xylene stink from the permanent marker filling the air.

But, he’s shaken the man’s hand.

And if he does not know now, after the shot and in the man’s presence, what then of the shot itself and the man again when Dan will, months hence, witness him behind his wife and will see her, hair caught up and balled in Clive’s fist, pants around his ankles and her summer dress pulled up all the way to hang a single breast, alive like in her stories told in the narthex all those tender years ago—“…I always just liked the hunt, I suppose. That’s what it was for me, hunting, and it didn’t matter what I caught and, fuck, I mean, listen, I remember my Uncle telling me once about when he was a kid and he would go hunting because they had a big farm. He said they’d go out in the mornings while the fields were still wet and they’d bring their guns, his brothers and sisters I think, and all go out and shoot the rabbits coming out their holes, the birds on the fences. They’d shoot at the deer if they saw any, but, and he said he was sad about this part but that he didn’t know any better because he was just a mean little kid and it was always on Saturdays when their Mom and Dad were asleep and so there was nobody to stop them, but their guns weren’t like big enough, you know? Like they didn’t have, I don’t know what the terminology is, but they were the kind of guns that you’d give to kids go shoot stuff with, like cans and rabbit and birds maybe but not deer, but they’d shoot at the deer anyway the deer would all run off with holes in them and sometimes they’d see the same deer again and it’d run away before they could shoot it but, there’d be little black or brown splotches or scars in their sides and legs and he said sometimes their faces but the deer were always there, they’d come back, but that’s not the point. Anyway, sorry, I asked him did they eat the things he killed and he said no of course not we were just mean little kids and sometimes we didn’t even kill everything we shot, not just the deer but sometime the birds and rabbits and opossums and mice and hawks and turkeys and chickens didn’t even die and the only thing we didn’t ever shoot were the cows and goats and dogs and sometimes we shot the cats because there were so many of them in the barn every summer and they didn’t even always die but we would still hunt them. And I remember I told my mother about it when I was a kid and my Uncle told me all this for the first time, maybe the only time maybe, but I told my mother who hated my uncle and always said she’d rescued my father from that family, and she said that that’s not hunting. She said that that’s just shooting…”—and Pastor Dan will nod and make his face as to smile at it all, lean in the doorway a moment long, heart settling, his silence against her cries and Clive’s grunting a prayer if there ever could be something so sweet.

Yet still, the gun finds its way: Off with a sound like before anything was or could have been, that great suddenly from which everything follows, a now made then and felt forever on, and afterward in the calamitous unending moment of life lived through to what will only be because it must, there’s no other way now and, if the man Dan knows his God the way he claims, there never was a way to be other than this. But, it should be louder. In his mouth the gun’s going off should be, by all possible reason, the only sound there’s ever been. What follows the trigger, though, that simple reaction, the easiest thing the world, the only thing in it at all, is an impossibly quiet silence—the sweetest prayer there could ever be. And it is all there is left to be. This quiet resounding, blooming a black absence to the edges and it’s all just beautiful and gone like before God set to count to seven and make it all Good, like before the Man was to speak and make it all different, like before the side was taken to make another like him, like before God and the Man stood in the final mistake of separation that put it all in motion and made everything possible impossible against nothingness. The way it all should be—lightless and without and all that could be and would be and must be and ought to be not yet at all, the way it should have stayed but couldn’t or there’d be no thing larger than to mark out the small from itself, there’d be no thing less than to delimit the more, no thing grand or few, all a burbling purple potential—and so, in the gun then, in the metal and darkness of the chamber, barrel rifling dim against chin skin, there was allowed for a flickering moment, long enough for a yet unmade world to declare a day, a spark of unseen light.

And it was Good!

And it will be Good!

And it is Good!

Why then, gun going off and all the seizing silence, would God speak this way? And, further, how is one to keep quiet when God has demanded His answer? Kind as the voice must be, it’s still a demand when there’s nobody else around—and there is forever and now nobody else around! Even when she erupts, cutting through the middle in the Man’s sleep, she’s still only him breathing differently. But God sits the Man on a rock, though neither are yet called anything but Good and Likeness and Image, and parades before him all there is to parade and says call it by some name and, surely, the Man must have said it the way he’d heard it from God Himself and called everything—though it’s absent from the text now and there’s readings upon readings upon readings that’ve tackled this moment that should never have been but had to have been since everything that was is and will be and there’s fuck all to be done but fire the fucking gun because it’s got to go off at some point and every point is now, now, now—Good and like God Himself, so God had to have, must have—and here’s the true Fall if there ever was one, of God and man in tandem, the only thing to rise the made-world as fact and difference—said to him that it wasn’t at all Good, that it needed to be called by a name other than Good and like God in image and so the Man opened his mouth and, tongue loosed in speech for the first time, unpracticed and wet and slow, stumbling over it’s teeth and cramped by the cave of cheeks, spoke all the names of everything.

And the man should have kept his goddamn mouth shut. Out of all the Goodness and Likeness of God, sudden noise, and everything a thing unlikened from itself. A body severed, and all the juice spilling. God standing there in the garden—and now it’s a garden! Not just the place in God where God and the Man like him can stand side by side or sit by the water or upon the rocks and see the appearance of things without any need for knowledge of what holds it all together!—, and every name sends Him further away from Himself and Goodness and suddenly, somewhere in the list, it must have come to be known that now the garden was a garden and everything outside of it was welter and waste, just as it had been before the light and Goodness that created always and all possible ways against the singular way things must now forever come to be, and everything was now other than God and—sure, sure, sure, now there was definitively a God, but only against everything that He is not and the last thing to do, that must have had to have been done was to give the only thing with no Likeness left, given that God Himself was now un-of the world He’s made and likeness to Him is likeness to nothing, something which to share in Likeness with. And there she was and she learned the names of things just as wrongly as he’d named them and they all forever, all of them, will call everything by the wrong names as wrongly as each other and will call it the world and everything, and God is far away for all their calling everything anything other than silence!

So, the gun finds its way and goes off with a sound like quiet. And the quiet explodes in flesh and threshes mind toward stillness. But all seizing aside, there’s little to do about a name once it’s been named, the thing cannot be made same as all other things without first a thing with which to share Likeness, and without Likeness at all, in a world of sputtering and Godless difference, there’s only—

“Danny! Danny!”