For Sale, Creator’s Throne, Never Used: A Narrative Of The First Age

For Sale, Creator’s Throne, Never Used

A Narrative Of The First Age

This piece is a response narrative for the Autofiction x Worldbuilding submissions call. It was inspired by this Autoficitonal seed. For this call, we asked people to write a response to another author’s autofictional submission, based on the original piece and this bit of cryptic world lore.

This, and other Worldbuilding pieces are being published to a Wiki, which will allow contributors to edit, link, and otherwise annotate their work and that of their peers.

The Manufactory of the Dawn, goblins run it now, that’s what I’d been told. Probably getting into a lot of trouble. I know all about that, I’m a goblin too. I’d picked up the sloth-construct cart from where it had been left. Didn’t see the driver anywhere about. Cargo got to move. Just hitched up the beasts, put on the cap that had been left on the drivers bench and patted the furry creature sitting there. Away we went, down the road.

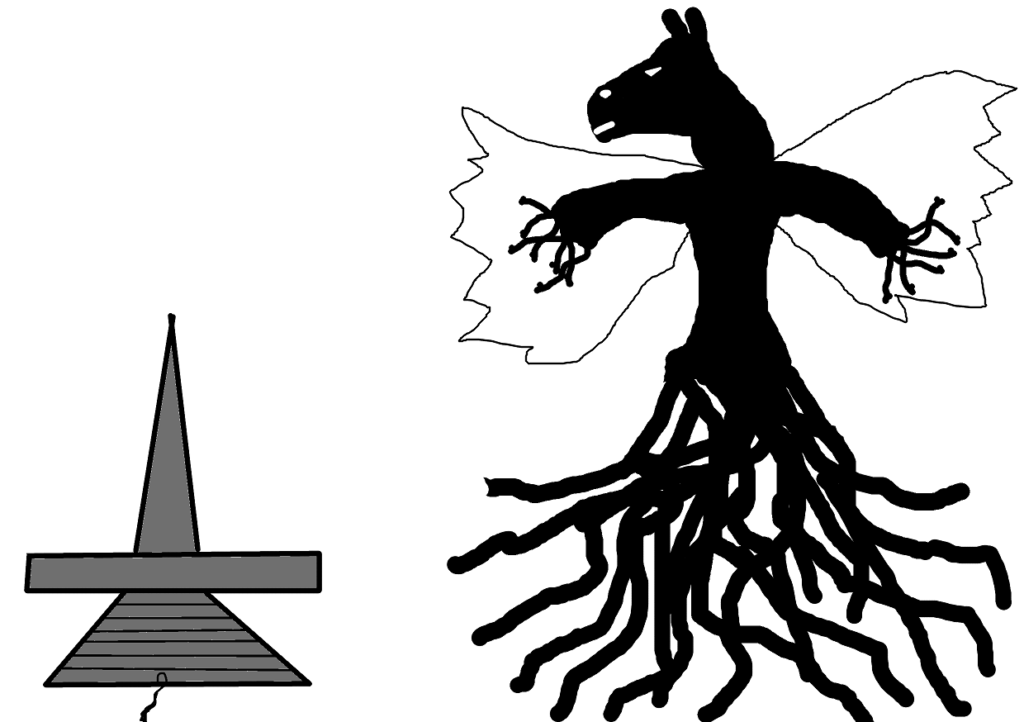

The Manufactory could be seen for days across the plain. The base was like a mountain, though closer you could see it was layers, terraces, a ziggurat seven levels high. Above that a big wide level, horizontal, overhanging the base, a clear sign that this was no natural landmark. And on top the tower, like a great blade pointing at heaven. Here and there thin plumes of smoke escaped. At night mysterious orange glows could be made out, scattered across it.

In the mornings when I wanted to be sleeping it blocked the sun. But necessity drives us, the brazen sloths did better in the shade than the heat of the day. I did too, and so did my furry companion. We made our way along the road, one of many carts and wagons crawling across the plain, me napping when the sun slowed us down, waking when it cooled in the night. Shortly after dawn we arrived.

The gates stood open, higher than any building I’d ever been in. A goblin stood between them watching me. He held out a hand to stop and I tried a variety of commands, the sloths slowing down and eventually settling only a few yards beyond him, so one of the control words must be right.

“All right, all right speed demon. No need to hurry. Governor’s not watching,” he said. “So, what you hauling.”

I looked back at the sacks piled high. “Just what it says on the manifest. Rice and beans.”

He didn’t ask me for the manifest. “Rice and beans together, or rice in some sacks and beans in the others.”

I looked at the sacks again. I began to doubt it was rice, or beans. Changing my mind now would just cause this guy trouble. Looking at him, ragged ears, skin flaking from too much sun, he’d had trouble enough already. “Rice in some sacks, beans in others.”

He turned to look into the darkness of the cavern. Within was a poorly lit enormous tunnel that got gloomier the further back it went. I shaded my eyes to make out goblins and wagons, moving back and forth, heading for stairs and tunnels and corridors. The interior of the Manufactory was honeycombed with passages and rooms.

I should have figured that out myself.

“Well over there, that’s the tunnel to the rice bunker. And there, that’s the way to the bean cellar. Pick one and unload, see what they want to do with the rest I guess.”

“Thanks pal,” I said, looking down. He peeled a long strip of dry skin from his head. I took pity on him. “Here, try my cap. Keep the sun off your head.”

For a moment he looked like I’d insulted him, or maybe insulted his mother, though if he knew his mother he’d be the first goblin I’d met who did. “Okay then.” I passed it down and he put it on, looking faintly ridiculous under the brim. “Yeah this will be good. Thanks. You’re a real gent, generous as the goblin king.”

I always like to be helpful.

I kicked the brazen sloths back into movement. The tunnel had a great plaque above it, with sigils or runes or glyphs, all carved out the stone, or maybe forged of dark metal. Too high to get a good look. Below has a single large symbol that was unfamiliar, one of the old languages, Enochian maybe or Ogham or Lingua Ignota. And hanging from it by a bit of string a wooden sign with a painted picture on it. A wheatsheaf I would have said, a grass stalk. The goblin at the entrance said it was for rice, so rice it was.

Maybe the painter wasn’t very good at painting. You’d hope they could find a good painter somewhere in the Manufactory. Probably busy elsewhere.

At the end of the tunnel I came to a great chamber, goblins moving sacks here and there with wheelbarrows, the whole lit by glowing orbs in the ceiling. “Hey there,” called a goblin, a big guy. His striped vest glowed in the light. In one hand he held a tablet. Wax, I thought to begin with, then as I managed to stop the brazen sloths I saw that there were pieces of paper on it, trapped by a metal clasp at the top.

“Let’s see what you’ve got here,” he said and vaulted up onto the cart before I could stop him. This disturbed my furry companion who hid under the cart.

I checked the sloths were staying in place. By the time I turned he had his knife out and cut open a sack. “Coal,” he said meditatively. “Coal. We don’t usually handle that here.”

“Oh, the guy at the gate thought you did,” I said. “Hey, I can turn around and go back if it’ll cause trouble.”

“No, no,” he said, poking at it. “We can handle anything you know? The Governor put us here, there’s nothing we can’t handle. Anything under the Throne Of The Creator, that’s what we deal with. Coal, coal.” He thought for a moment, then riffled through his papers.

He stood tall and shouted out. “Okay listen up.” A few goblins drifted closer, some bringing empty wheelbarrows. “We got a load of coal here. We’ll send a message up the tube, let them upstairs know what’s coming. We know where it goes, sacks on the hooks, then ring through to the belt office, get them to turn it on. It’ll be pulled away through the shafts, to be dropped where ever needs fuel.” He gesticulated wildly. I saw where he pointed to when he talked about the hooks. A whole bunch hanging from a belt that wound around a big spindle, then turned to go upwards, diagonally, the belt itself vanishing into the wall.

As he organised the work party I thought to myself I’d done enough here. Maybe it was time to see where else I could help.

“It’s been a long trip,” I began.

“Yeah yeah, I got you. We’ve got all the requirements, and them fit for the goblin king. Now see there, the outline of the goblin shitting? That’s the latrine.” I looked, and from a great plaque of symbols hung the latrine symbol. “The one of the goblin washing? Bathhouse. The goblin sleeping, that’s the bunks. And the gobblin eating? I reckon you’ll figure that one out.”

I did. I relieved myself in the latrines, and I washed myself in the bathhouse. In the changing room I found a clean set of clothes, including an orange vest that made me highly visible, a hard white hat and a tablet with a clip holding some papers and a pencil on a piece of string. I put them on, it was almost as though they’d been left for me, they fit so well. On the breast I put a badge, one with an old sigil on it, one that looked like a throne.

In the canteen there were a handful of goblins scattered about the tables, and three at the stove. I went over and greeted them. They seemed eager to please.

“What would you like sir, we have plenty here,” said the first, thin and pale, pushing a basket of crusts and crumbs my way.

“Give him a tray and a bowl,” said the second. “And yes, plenty, but not too much, no we’re not wasteful, your worship.” He had a basket of dried fruit that he put on the counter.

“Enough of that, a hot meal, that’s what the he wants I’m sure. When he reports to the Governor he’ll say we feed people up properly, won’t you captain.” He put some fat in a pan, then the pan onto a metal plate. It hissed and sizzled. He held his hand over a basket of eggs, chopped onion, some large mushrooms, and cut up roots and vegetables. “What’s your pleasure sir.”

“You’re the chefs,” I said and a moment of panic swept over the three. “You’re in charge here, you don’t need to call me sir. Make me your speciality.”

They made me Eggs Gobolino, a great pile of everything bound up in eggs. Pretty good, even with the shell and burned bits. The furry creature returned , sensing a meal time, but wouldn’t eat it. A mechanical snail slithered around, waste bins hanging from its shell, and I discreetly put the portion I couldn’t finish in.

When I saw the chefs watching I made some notes on the papers on the tablet, the eggs recipe and a picture of the snail.

“Was it good your highness?”

“Very good, very good. Don’t call me highness.”

“I suppose you’ll be going upstairs.” The three of them looked over at a red door. A threatening sigil was above it, perhaps a double-headed axe, or perhaps a boar’s face.

“I suppose I will,” I said. I didn’t want to disappoint them.

Through the doors were stairs, possibly carved out of stone, made or molded in place. As I climbed them one wall opened up and I found myself above the cavern I had been in. A big cart pushed by an obsidian bull had run into the back of one with brazen sloths in front. Goblins clambered all over the two, checking for damage, calling to each other, offloading the cargo. The one with the clipboard and vest I’d seen before was waving his finger at a skinny newcomer, who in turn was shouting at the sloths. In the echoes of the high vaults and the clicking and clacking of the moving belts it was impossible to make out what they said. Just before I climbed out of sight he kicked at a brass sloth and yelled a clear curse.

The stairs turned and twisted, moving through the solid structure of the Manufactory. After climbing far enough my knees began to complain and the rest of me regret I did not bring a drink with me I came to a landing. In one corner was a latrine and water fountain that I took advantage of, then investigated further. Here sixteen stairways met, each with a tube alongside that connected in a complex set of junctions. Four stairs went down, and four up; the others appeared to turn off in some uncanny direction. The closer I approached them the more normal they appeared, simply steps that happened to head off in a dimension not normally accessible.

The glyphs on them were as mysterious as ever. One did have a goblin-drawn label; it appeared to be a frog seen in all directions from the inside out.

I rejected them, turned back to the usual directions. I discounted the four going down and considered the others. A relatively simple set of right crossed blades, or a wheel, and below it a stylus on a piece of board caught my eye. As I considered the furred creature joined me, then went and sat on the bottom step.

I mounted the stairs, the creature following. After passing through several strata of different coloured stone the stairs emerged into an airy space, lit by great beams of dust-flecked sunlight. Out of reach were catwalks and stairways, poles and ropes, great girders. The sounds were muted, there was movement on some distant ones but none close enough to make out details.

The stairway zigged and zagged, was encaged in metal, then released again, now flimsier, gaps between stairs. I climbed steadily, finding that I was alongside a vertical belt hoisting sacks upwards. Just before the increasing thickness of girders became a ceiling the stairwell turned around the belt and met a doorway.

There was a knocker which I knocked. The door crept open to reveal a silver ape construct. The mechanism beckoned me to follow, and we travelled through a maze of narrow passages.

At another door, the ape knocked, then let me through. I found myself in a great chamber. Before me was a silver claw, five times the height of a goblin, easy to measure as a dozen goblins festooned in polishing rags climbed over and around it, polishing with wax and cloths where the previous goblin had just been holding on.

I marched up and cleared my throat, then again louder. “Who’s in charge here?”

A goblin with a spectacular boil on his nose looked up, wiped the sweat from his brow with a cloth. “Chief’s round the corner, dealing with some cock up,” he grunted, then went back to polishing the boot print of the goblin just above him.

I circled the claw, the heel spike blackened with filth, to find chaos. A tall goblin with a shock of white hair spilling out from his helmet was shouting, waving, pointing with a spanner. Around him were other goblins, some staring with mouths open, some working on a piece of machinery, others carrying sacks, one pushing a broom across the floor, moving slowly around the standers and the runners.

A couple of goblins were trying to sneak away, dragging a sack between them. They looked up and saw me. Stopped, a look of horror on their face. The orange vest, the white helmet. The badge. And worse, the pad of papers.

“Names?” I said sternly.

“Chokejam, your worship.”

“Petanque, magister.”

I looked at the sack. Beans dribbled from where the stitching had been cut. The furred creature sniffed at them and licked itself. “Do you have a chitty for this?”

The two looked at each other, then back to me. I waved them on and they fled, scattered beans falling behind them, the furry creature looking curiously back and forth at them and me.

The tall goblin saw me, nodded and continued ordering goblins about, some of whom sprung into action, others stared blank-faced.

“What seems to be the problem chief,” I said when he paused, waving my board at the work being done.

“Some god-forsaken arse down below sent sacks of coal up the belt, without a warning for the inter-connectors to be re-aligned. There’s a system, you send a message up the tube, you ring the bell, you pull the telegraph, then the goblins on the switches set up the tracks and belts, then they ring back. All before you set it going. Then your bastard coal goes to a coal bunker, and does not get sent to be dumped in a grease tank.”

He pointed at the heart of the swarm of workers, most of them standing about holding tools or parts, ready to hand them up. The belts and hooks met at a complex six-way connection. “Now the good news is that some clever bastard was awake up there, saw what was going to happen. Coal dust in the grease, we’d be weeks cleaning the tanks out, then have to refill them from scratch. A whole lot of wasted grease, a herd of oil-bears.”

I perked up at this “Oil-bears? I thought they were a myth.”

He frowned at me. “I asked a goblin where the oil he brought came from. He showed me the barrels, sealed with a bear stamp. They hunt them by the West Pole. Land of swamps and fogs. The oil bear sits on top a stalagmite in the marsh above the mist, listening out. When it hears something moving it reaches down with an enormous paw to catch irey. What the hunters do is set a trap. The bear’s paw is caught and they can cut it up with hatchets.”

“Doesn’t sound sporting,” I said.

“The hell with sporting,” he replied. “You know what would happen to this place without grease?”

I nodded. “The engines of creation would grind to a halt. No more constructs. Civilisation would fall and the First Age would come to a shattering end.”

“We would miss our targets and the Governor would be bastardly angry,” he said. “And that’s why the goblins who hide in the mist and slaughter oil-bears with maximum efficiency and minimum risk to themselves are god damn heroes.”

I decided it was time to assert myself. To contribute something. I picked up the pencil on its string and licked the point. On a blank corner of the paper I sketched an oil-bear as best I could having never seen one. “God… damn… heroes.”

The chief looked me up and down, then down and up. He came to a conclusion. “And what are you doing here?”

I pointed the pencil at the tangle. The goblins there were fewer now, some escaping the gaze of their supervisor. Those remaining worked frantically. “The coal came up the wrong track.”

“That’s right. As I said, some clever bastard saw and pulled the emergency stop. All good. Except an emergency stop knocks it all out of joint. Whole lot of trouble One belt slows, another jumps, sacks ram into each other. Next thing the whole interchange is jammed, spilling rice into the gears. With the interchange out, everything that depends on it is at a standstill. The whole west shaft is frozen. This knocks on; the grand trunk taking up the slack. The overspill from the lower levels is sitting waiting, the east shaft is at capacity, even the north is having to start moving properly. Good, serve the lazy bastards right. But that’s not what you’re interested in.”

On the contrary, this was very interesting. It was pleasant to hear someone who knew what they were up to explaining it in plain language. I didn’t want to argue with him. “As you say.”

“Right.” He turned away, pointed at the smallest goblin I’d seen since I first crawled out of the breeding pits. He scuttled forward holding out a jacket and scarf to his Chief. “No, give me the rag first Mervile! I don’t want coal dust on my good clothes.” He shook his head. “Sorry about that. My great-nephew you know. This generation.”

The goblin squeaked at me, finding a grimy polishing cloth from about his person. “He’s wrong sir, I’m not a relative. I worked my way up from lackey to dogsbody to batman and now here I am, amanuensis to the forge master himself.”

“You all look the same,” said the forge master dismissively. Voices stopped. Goblins stared. “I’m just saying it as I see it.” He wiped his hands clean aggressively, put on the jacket, tied the scarf in a flamboyant knot. He froze. “What is that… that vermin?”

The furry creature had returned and wove between my legs, then sat down and looked up curiously. I returned the look, “Not vermin, a feline safety auxiliary.”

“Ha. Health and safety gone mad. They won’t catch me out though. Mervile, this cat is a worker. Get them a vest.” He stalked away, calling over his shoulder. “This way.”

“How do I…” began Mervile.

“Measure the cat up, run to stores. We’ll be touring the forges. Catch up quickly.”

Mervile pulled out some string and tried to run it around the cat’s chest. It hissed and arched it’s back. Mervile took measurements from a distance. I turned to follow the chief, the cat trying to trip me as I walked. A fun companion.

Past the belts the sounds changed. From the groans of cloth and leather we could hear the scream of hot metal and the clash of tools. The forges. As we approached I got hotter under my jacket.

The machinery reached from floor to ceiling, enormous shafts and conduits entering each section. The chief yelled out. “The shaft to bring in sweet air, and the one to expel foul. The coal chute, the water pipe. Here is where the ore is delivered, there the flux. Solder of course, three different types. Limestone. The acid jars. The buffet and drinks tray. And of course the…” The last was cut off by a shattering whistle; I could see a goblin trotting through the door. Another latrine.

The whistle was a signal. The goblins all began to move, most of them towards the glowing, burning heart, stragglers rushing for smocks or tools. Goggles were put on, masks covered mouths, heads had helmets.

The chief tapped me on the shoulder, indicated the goggles on my own helmet, put his own on. I did and the world became inked in green shadows.

Not for long; the whistle cut out and there was a screech of chains and metal as a door was winched open. From it came a piercing, gleaming light. The heat was intense, the smell of water steaming off hot stone.

From the door came a finger of light. A rod of white-green fury, driving wailing goblins back. It reached and reached, the end turning slightly dark, then drooping just a touch to the curses of the chief beside me.

There was a shout and goblins pulled on levers and chains, some diving out the way. A dark shape emerged from the ceiling, curving down. It sliced off the end of the rod, then sailed back up, slowing. For an instant it sat, darkly gleaming against the green shadows then it came down again.

A pendulum blade, swinging metronomically, using it’s weight and momentum to cut the extruded cylinder of hot metal. Each piece fell into a tank to cool – and from the smell be oil-tempered.

Another whistle, another scream. The rod shuddered, stuttered in place. The pendulum axe cut, flicking a hot metal crescent out, goblins scrambling to avoid. Then it came to a rest, the door shut.

I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding. The cat peeked out between my boots. The chief raised his goggles; after I raised mine he led me forward.

Goblins were pulling the lengths of rod out the oil with tongs, one of them sitting to the side having a reddened hand bandaged. Each rod was held up, letting green oil drip off into a trough, then plunged into water. Taken out of the room.

We followed to a great workshop, metal tables and anvils scattered about. Goblins were wiping, filing, cutting grooves or grinding down the end of the rods.

“There you are,” said the chief. “Progress. Handles for the next batch of hammers and chisels. And so ready for the next stage.”

“The next stage?” I asked looking at my board. A smut had got onto the top sheet of paper, smearing over the symbols.

“Hammers and chisels to make the parts for the lathe and the drill and the press. We use them to repair the precision tool testing bench, the parts that hold it steady isolating it from the Manufactory’s vibrations. Then the precision tools can be calibrated to allow them to be used to infinitesimal accuracy. The tools then go to the optical laboratory where they etch glass for the micro-constructors. When we have those in working order it will be time to fire up the nanoforges. Project Typhon will then be back on track.”

The chief sighed deeply as a goblin dropped a rod on the floor, the sound echoing across the room above all the other sounds and chatter. The cat leaped up on a table and pawed at a paper package, unwrapping it.

“Hey, my lunch!”

“Not on the workbench Chadwick,” said the chief. “You know I wasn’t sure you were really a safety inspector, but look at that. Got to say, you went straight to the violation. And dealt with it yourself too, nice and calmly.”

The cat had knocked the package off the table where it had unrolled to reveal pickled fish, rice and beans, all wrapped in a leaf. The goblin who had lost his snack looked on sadly as the creature jumped down and began to eat it.

“What’s your name?” asked the chief but the cat didn’t answer. “What’s their name?” he asked me.

Mervile returned “I got hat and goggles and jacket,” he said. “For the cat.”

“Well put them on,” I said. “His name’s Jack.”

Mervile bent down to where Jack was eating the fish. The cat hissed. Mervile purred back, keeping away from the food, gently approaching, showing his hands. Letting the cat smell them. Then slowly, carefully dressing him.

The chief was talking again. “Yes, you can tell the engineers we’re on track. Making the tools to make the tools, to make the tools, to make the tools, to make the tools to make the world-wrecking blasphemous engine of destruction that is Project Typhon.”

I frowned at this. “Do we really want to build a world-wrecker?”

The chief looked at me sternly. He put his thumbs in the breast pockets of his vest. “We build what they send the plans down for. It’s not easy down here on the factory floor, not like up in a calm office, drawing diagrams on paper, having cups of tea every hour, on the hour, waited on hand and foot, like the goblin king. Aren’t you down from the engineers, looking to see how far off track we are?”

“No, no.” The sound of work slowed. “I’m from another department.”

The sound stopped. Everyone in the workshop froze. The muted hum of the Manufactory, the occasional breath and a mew from Jack as Mervile tied the hat string under his chin were the only noises.

“Another… department?” The chief seemed stiffer now. “As in…”

“I think you know which one,” I replied.

“Well then. If you’ll come this way, inspector.”

The goblins seemed to stand up straighter. The chief barked at them to get back to work but they just stood there. “Carry on,” I said. No one moved. Goblins used to manage without officers or nobles or a king. I put all the aristocratic hauteur that unneeded nobles and officers project so effortlessly into the words. “I said, carry on.”

They went back to work and we left. Jack followed, abandoning the snack.

Beyond the workshop was a small cage rising from floor to ceiling. Within it a basket. Beside it another tube. “The personnel lift,” said the Chief. “It will take you upstairs.”

“Thank you,” I said and went through the door, sitting on the basket. Jack jumped in beside me.

“If you’ll give my compliments to the Governor,” said the Chief. “When you see him. Not that he knows me of course.”

I nodded gravely. “I shall be sure to tell him all about you.” With a pull of a cord the basket began to rise.

Forge after forge, workshop after workshop. As I rose I could make out the patterns, the furnaces leading to the forges, then around to the next, swirling links making a spiral symbol that converged on…

The basket rose past the ceiling into a cool dark shaft and I could see no more.

We rose for a long time, Jack stretching then curling up. I considered doing the same but decided to sit normally in the seat. It was only polite.

At last the basket rose into another cage and came to a stop. There was the sharp ring of a bell and the door opened.

After the dim halls where goods were delivered and the noise and dirt of the factory level this was a paradise of light and air. Sun shone through windows, goblins in waistcoats and breeches scratched away at desks. Others stood around water fountains or at tea stands, talking quietly. The goblin who had opened the cage stood back; I dodged aside as a shiny black metal hog pulled a small wheeled cart, a long thin goblin passing out sheathes of papers to the workers he passed. A studious fellow with spectacles placed papers in a capsule that he put in a tube, closing the hatch and tapping on it.

“Well hello there… sir.” The goblin who had let us out greeted us.

“You don’t have to call me sir,” I said cheerily. “Nor the safety inspector there.” Jack mewed a reply.

“Well si… well then. After your time in the lower levels I am sure you would like to refresh yourself before continuing.” I blinked at him. “The washroom. This way.”

I was fairly grimy compared to the others here. Jack and I followed him around chest high barriers, goblins politely nodding as we passed.

The washroom was bright and polished, with silver metal and white ceramic surfaces. I cleaned under my nails, brushed my teeth, knocked dirt and dust out of my hat and clothes. Relieved myself in the latrine. When I offered to wash Jack he ignored me, preferring to lick himself and his outfit clean.

I looked at myself in the gleaming mirror. Did I appear taller? My nose sharper, my chin more solid? Dark eyes shining, my skin luminous in sweeps of green?

A goblin can be who they want to be, that was something I had been told. Or something like that. Yes. So I would be the goblin who found out what was happening here.

Jack mewed at an empty bowl so I poured some water in it; he pre-empted me, jumping on the counter and batting at the stream from the tap. After a while I turned it off, and ignoring his complaints went out.

The goblin was talking to a colleague; seeing me he broke it off and led me on.

To a large room, windows down one side, a long table in the middle. Three goblins were gathered around one end, all with dark serious-looking ties around their necks.

“Welcome welcome. Please take a seat.” The tallest one, his tie so dark a blue it was almost black. The escorting goblin pulled out a chair and I sat. He pulled out another; Jack jumped up, then on to the table and looked back. With some magnificent improvisation the goblin took a cushion from the chair and placed it on the table beside him. Jack sniffed at it, then deigned to curl up.

“Which project were you interested in?” asked the next, the plumpest goblin I had seen in the Manufactory, his tie a light-swallowing purple.

“I have seen Project Typhon below. We might start there.”

They all looked at each other and the third, so bland and forgettable that I had taken no notice of his features or his tie, he turned to the side. He knocked on the wall, three times, then four more.

In came two young keen goblins, holding a covered board. They placed it on an easel and then whipped off the cover theatrically. There it was.

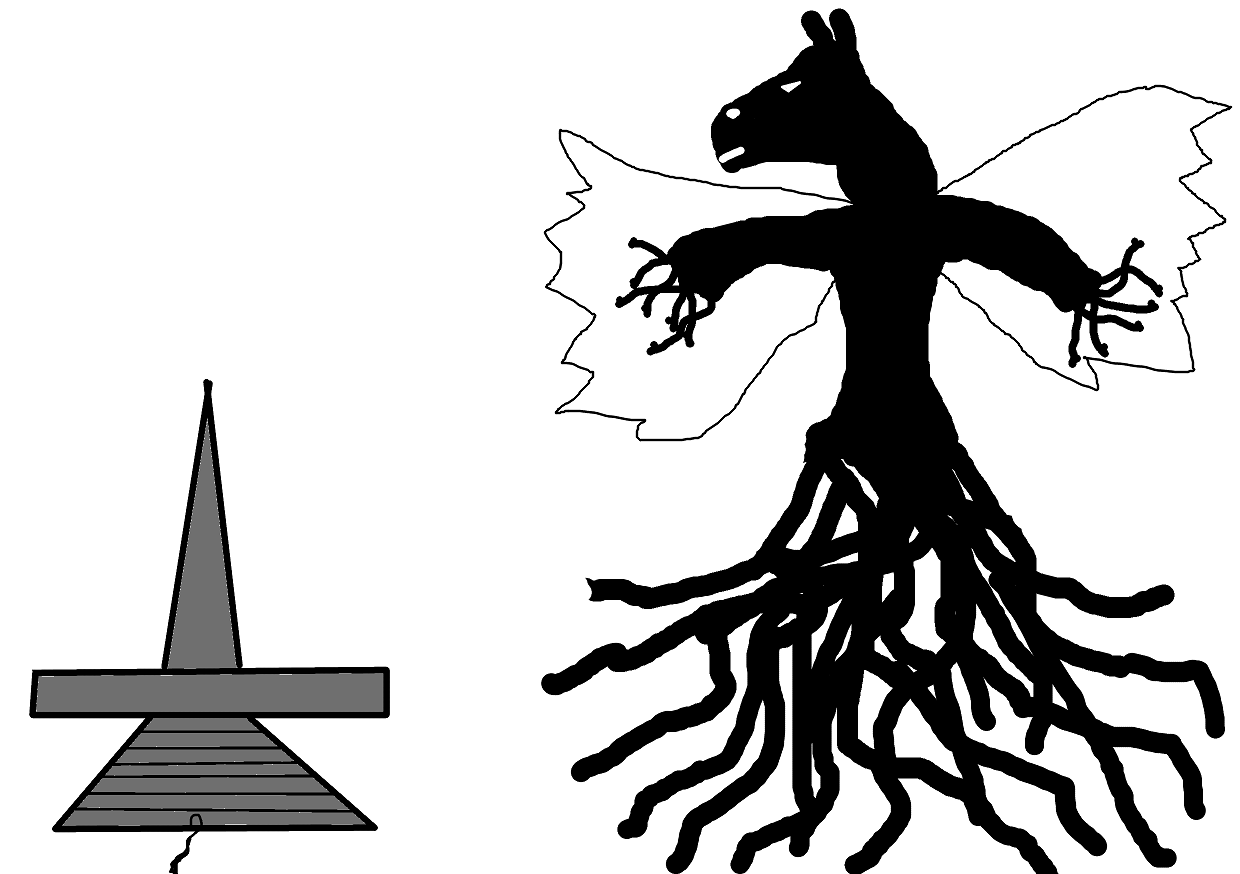

“Project Typhon, a melding of the most destructive elements of Mother Earth and the Incarnation of Tartarus.” One pointed at the boiling nest at the bottom, the artist’s work so finely done that I had to blink to see it was in fact motionless. “Below the thighs nothing but coiled serpents. His arms, when spread out, reach one hundred leagues, his hands made up of countless serpent’s heads.”

Jack hissed at this. I spoke up. “Serpent tails below, the heads on the arms. The divided parts connected by the body.”

The other had a pointer. “The ass-head…” There was a snigger from somewhere. He continued firmly. “The ass-head reaches up to scrape the vault of heaven. The wings darken half the sky. From the eyes come flame and from the mouth flaming rocks. That is Project Typhon.”

I looked at the picture of the world-breaker, the god-killer, the death of nations. A whirlwind of destruction, the flame of a burning earth, a serpent from the abyss. “What’s it for?”

The two young goblins grinned, looked at each other. Then turned together to look at the three senior ones.

“I assure you,” said the tall one. “This has been approved from the Governor’s office. By the Governor himself.”

Jack mewed. I shook my head. “My colleague is concerned about the safety of unleashing such a construct on the unsuspecting world. Can you tell me what it is for?”

The bland one shook his head. “I assumed form followed function.”

“If burning were our intention then there are other options, from goblins with drip torches, through fire arrows, all the way up to spitfires. If we wish to touch heaven then air-balloons and kites can be built. Serpents already exist.”

The round one looked on in distaste. “I always assumed it was for clearing land of unwanted obstructions. Forests, mountains, cities and so forth.”

“Very well. What next?”

The two young goblins rushed out, returning with a new board. This they unveiled with grins. “Project Python.”

An enormous writhing worm was depicted. At first I thought it limbless, featureless. Then as the goblins pointed out details it became clearer. The size of the construct was misleading; claws bigger than houses, teeth tall as a tower, they were dwarfed by the great belly and tail.

“By resting the main part of the structure on the ground there is a greater capacity for weighty internal braces and machinery. Python is therefore sturdy and robust. Well nigh indestructible.”

I stared at it.

“A hundred claws on each side to make it mobile, and remove obstacles from it’s path. Yet barely needed, the armour plates so heavy that they can push anything moveable aside, and slide over anything that won’t move; so finely balanced and machined that they will let it creep even without the traction of the limbs.”

I looked at the head, small compared to the rest, still enormous.

“Yes the head appears out of scale. This is because Python is a chthonic construct. As I said it can crawl anywhere in the world, yet there is more to it than travelling over mere surfaces. Project Python can burrow deep, right into the navel of the world. Crawl amongst the very roots of the earth, gnawing it’s way deep amongst them.”

Jack hissed at this one too.

“Serpents again. Do you think it safe to have such a fearsome, unstoppable construct undermine the foundations of the world?”

The tall one spoke. “I assure you that, this, like every project developed by the engineering department, has been approved by the Governor.”

I scratched my chin. “So before it is developed he approves it.”

The round one nodded. “That is so, in every detail.”

“Yet until it has been developed he cannot know the details, so how can it be approved of?”

The bland one smirked a little, polished his quizzing glass. “We are in constant communication with the Governor’s office.” He pointed to the tubes.

“Pneumatic?” I asked.

“Ferrets push the message capsules.” Jack sat up at this.

“I see,” I said.

“Project Python could excavate waterways, harbours, dig mines?” The tall one’s air of competence was fraying rapidly.

The two young goblins took this as a cue and rushed out to bring in another. “Project Hypton,” they said proudly.

This appeared to be a great butterfly with enormous eye-covered wings. The eyes, it seemed had multiple uses. Some could be used to watch what went on below when the sky-darkening presence of Hypton flew over, out of reach of the ground-hugging mortals. Others could see deeper, into their minds, reading their thoughts, uncovering their secrets. And a few were even more active, able to overwhelm the personality and will, making them behave as Hypton wished.

“How will Hypton wish them to behave?” I asked.

They pointed out the long proboscis, so Hypton could suck up water or food without ever landing, the tentacles to grasp birds and insects from the sky, the jagged wing edges to cut through any enemy who might climb to meet it.

Jack gave a yawn and they brought in another board.

Nopyth, an obsidian block that at first view seemed featureless, the artist’s rendering sucking vision in, black on black on black. Very slow moving and growing it was nevertheless unstoppable. Creating a wall that would divide the land. If anyone attempted to cross or damage Nopyth, the many mouths would tear and other orifices let loose corrosive fluids to dissolve and rot the attacker.

“Which places do we need to divide from others with such great ferocity?”

The roots dig down to bring up nutrients… the board was replaced.

Photyn, a brazen bull who reflected sunlight so powerfully it would blind those who looked up it, with fiery breath from the nostrils, hooves that could break castle walls.

Tophyn, a sea serpent that could swallow fleets, eyes that disorient sailors, a tail that could make waves that would smash down cliffs or devastate the land for miles inland.

Phyton, a plant that grew upon itself, a stem and lead on stem and leaf on stem and leaf, shading the land. I showed some interest in this but they were on a roll.

“Here is the masterwork. Phonyt. This is expanded one million times.”

A change in scale at least. Rather than a creature of great size, this was tiny, invisibly small, infinitesimal. I peered at it. It seemed to be made up of gold lozenges, so finely drawn that I could swear they spun and twinkled, the whole seeming to expand and shrink, move across the page.

“Phyton can stay dormant for years, yet remain viable. When it finds itself in a host it will move through the body, causing no trouble or symptoms until it finds itself in the brain. Even there it will only activate in a pre-frontal cortex. So only in sentient beings such as goblins, trolls, gnomes, rabbits, dolphins, merpeople, angels, devils. Possibly some of the more advanced apes if you can believe it.”

The goblins at the head of the table smiled at each other, wide, toothy grins as though they might be about to sit down to a delicious dinner. Jack sat bolt upright and hissed, then spat.

“And what does it do?” I asked them.

“Oh very simple.” The round goblin seemed pleased with himself. “It burns out language, word by word. Completely removing the ability to express or understand.”

I stroked my chin. “Seems like something that could easily get out of hand. And go on to destroy all culture and civilisation.”

The tall goblin looked even more satisfied. “Fortunately the researcher is close to making a counter agent. Or so we believe, it has recently become impossible to understand him.”

The bland goblin shrugged. “If it becomes a problem then that is what the other projects are for. Scrape the world back to a blank page. Let the Creator mount their throne and try again.”

I nodded. It was becoming clear at last. “So not your problem what happens after these projects are built.”

The tall goblin grinned. “We have developed these plans from the outlines and requirements that were left here for us. The strategic use of the projects is for higher governance.”

The round one puffed his cheeks. “We do as we are assigned and as we are authorised, under the authority granted from the Governor.”

The bland one had no expression on his face. “And I must at this point note that these plans are approved, and also by granting that these constructs are self-governing, absolve us from all responsibility as to their actions.”

I stood and the other goblins stiffened. “Well thank you gentlemen. This has been most enlightening. I think that I will make my way to the Governor’s office.”

At my movement Jack started, then bounced forward. One of the young goblins tried to intercept, the other to get out the way. They ran into each other and collapsed into a pile of flailing limbs. Jack sailed above them and landed with all four paws on the near vertical board, claws digging into the diagram of Phyton.

“Get the broom,” croaked the tall goblin. “Get the broom!”

I shook my head. “Leave Jack alone. As Auxiliary Safety Officer they have some criticisms of this project.”

Jack scrabbled violently, then slid unceremoniously off the bottom, turning in midair to bounce off the squirming goblins and trotted back along the table, tail and head held high. I stuck my head out the door and found the escort standing there, elaborately not listening in. “If you can take me to the Governor’s office please?”

He took me through the corridors. Now the goblins either turned and ran away or stood and stared. No one pretended to work as I went by. Part way through Jack came bounding along, passed us, then slowed to a trot, leading the way.

We turned a corner and found ourselves facing a moving stairway. Jack looked at it, looked at me, then came back and weaved around my legs. I bent to pick him up; he chose to climb and position himself as a lookout on my shoulder.

“Well your honour, if you go up there you should find your way to the Governor.” He gave a smart salute, which I returned much less smartly.

“Is there anything you’d like me to tell the Governor?”

This seemed to throw him for a moment. “I ah. I’m very proud to serve here. Sir.”

“I asked you not to call me sir. I’m no officer.” I left him to his confusion, stepping on the first tread, grabbing hold of the moving handrail as my foot was dragged away.

Once I had my balance it was a very smooth journey. Jack had dug his claws into the vest’s padded shoulder, almost as though it were designed for this. I looked down. The plan of the engineers’ offices could be seen from above. They watched me ride up as I saw how the desks and meeting rooms were arranged, like a labyrinth, circling and funnelling towards a centre.

Up through the ceiling, the eyes now hidden. Everyone had been thinking about the Governor. As though he were a king. The one goblin who knew what was going on. The one goblin who had answers. The one goblin with the power to loose and to bind.

The one goblin with the right to call me out. The ability to say, you belong here. Or you don’t belong.

We’d meet that when we came to it.

The moving stair approached an end, the steps vanishing under the floor. I hopped off, and only when safely on solid ground did I look about.

A great vast hall, an empty desk right in front. Beside it were a dozen or so tubes, the ends beside a basket overflowing with message capsules. As I watched a capsule emerged, bounced off the top-most one of the pile, then rolled away onto the floor. A small white face came out. Jack stiffened on my shoulder. The ferret ignored him, ignored me, instead and ran across the floor to a small hole.

Beside the hole were double doors, three times the height of a goblin. The doors were ajar and from inside came a rumbling. I looked at Jack, and he was looking at the hole. “You do not want to go in the ferret hole,” I said.

I went through the door.

A hall that was like the one I had come from, but the desk was twice the size, behind it a great brazen mask, and beyond that windows, opening onto the world beyond. As I came in the mask grunted, steam coming from the ears. Jack leaped from my shoulder and ran.

“Not the ferret hole,” I called out.

“Pay no attention to the goblin behind the curtain,” said the mask, as Jack ran to a curtained alcove. I stamped after him as he wrestled with the fabric. I picked him up but his claws were tangled and pulled it aside.

Inside was a goblin, sitting on the latrine, reading a bundle of papers and smoking a complex looking pipe. “Don’t mind me,” he said.

“It’s me you’ve come to see,” said the voice from before, much less booming now they were out from behind the mask. A smart looking goblin, eyes bright though the wrinkles of age covered every part of his head. “Let my secretary deal with his business in peace.”

He took a seat behind the desk. Jack was reluctant to release the curtain so I left him to it and found myself a seat without being invited.

“I know why you’re here,” said the goblin, the Governor. “I know why you’re here and I want you to know that I disapprove.”

“I see,” I said.

“When I was young we were all just goblins, one squalling undifferentiated mass. I see no need to maintain these artificial distinctions. A goblin is a goblin is a goblin, that was good enough at creation and should be good enough now.”

I inclined my head, then had to adjust the goggles that threatened to slip down onto my face. “As the Governor, surely you have the power…”

“So why divide goblin from goblin? Why declare some male goblins and some female goblins? What purpose does it serve? At least the current system, where each goblin expresses their preference can be comprehended. The first attempt was a shambles. Trying to categorise the manifold infinite grotesque variety of goblin genitals into two classes. Impossible, ridiculous, and quite disgusting.”

He stared at me and I stared back. “You said you know why I’m here.”

“Well of course. Having divided goblins in this way categorically, it seems that we must divide them physically. Male goblins go to the Manufactory of the Dawn…”

“Females to the Manufactory of the Dusk, and those who are neither join the aeronautical corps. This is known.” I stared at him and now his wrinkles seemed to deepen. “What I want to know is what is going on here.”

From the alcove came an odd whistle and a quick burst of vapour. Jack came sprinting out. When he saw us watching he slowed to a casual stalk, obliquely sidling towards the desk.

“I am the Governor you know. I am in charge.”

“Then tell me what is going on,” I said. “So many goblins working hard to create frightful engines of destruction. Is this really what we are about? Do goblins want to be known as such monsters? Is that to be our legacy.”

He sighed and held up a slim volume on the desk. “Do you know what this is? Of course not, you’re not the Governor. When I arrived here I found this office and this desk. And this book. The other goblins wanted leadership. They needed to be told what to do. So I deciphered what I could, as best I can and sent down the instructions.

“In this book are the notes of the Creator. Everything that they intended for this world. And all my attempts to bring forth a design have led to building a great construct. Will it be a terrible destroyer? Well, such is not my business. The Creator left his notes and who am I to deny them.”

The Governor had deciphered the Creator’s notes, or six letters of them at least. Jack jumped up on the desk and mewed quietly. I stroked him with one hand, adjusted his jacket where it had rucked up with the other.

“You’re the Governor. You took charge. It’s your responsibility.”

“What, was I supposed to leave this office empty?”

I sighed. “Why not? Do you think that by setting yourself above other goblins – apart from them – you’ve made things better?”

The Governor stood up then. He put all his officer class strength into his voice. “Goblins need leadership. They want leadership. They love to be told what to do. And I gave it to them. If I did not take this seat, this office, someone else would have. And who knows what they would have done with the power!”

“Project Typhon? Project Hypton? Project Phonyt? Goblins want work and purpose yes. They don’t need a Governor who has them make world-ending weapons.”

The Governor shrugged. “Well so long as I am on this side of the desk it’s my opinion that matters. It’s not as though the incompetents down below would be able to complete projects of this magnitude. Even the Creator left before finishing.”

I raised an eyebrow. “What’s upstairs?”

He froze, then collapsed into his chair. “You’re kidding of course.”

“I’ve come this far. I want to see what’s up there.”

The ladder had been badly disguised, some sheets hanging from the bottom two thirds, the upper part in shadow.

“The throne of the Creator… but no goblin would dare…”

I looked him in the eye. “Do you think just any goblin could make his way into the Manufactory. Visit every office, every workshop, every store and canteen and washroom? Be welcomed at every turn, even here? Do you think that one of the undifferentiated mass of squalling goblins could make their way here in front of you?”

“Your Majesty…”

“Stop that.” I stood and Jack mewed plaintively, squirmed onto my shoulder. “I work for a living. And so should you. Do you know what leadership is?”

“I, I mean…”

I made my way towards the ladder. “Well, I’m sure you’ll figure it out eventually.”

I pulled loose the sheets and began to climb. From below came the voice of the secretary. “What now Mr Governor?”

“Wash your damned hands Gruntlespoon!”

****

In case you didn’t know, the Creator didn’t leave a throne on the pinnacle of the Manufactory Of The Dawn. No throne, no crown, no sceptre, sword, wand or orb. Up top there is a shelter with cushions and blankets. A water spigot and cooking stone, pots and pans. Dried fruit, dried meat – Jack went straight for that. Bags of rice and bags of beans. A latrine of course, and a farseer.

There’s no throne up there, no king. I looked through the farseer and saw how the creatures of the world were continuing the work of Creation. Trolls piling rocks into mountains. Gnomes digging out waterways. Goblins burning forests, planting saplings in the blackened remnants. Herds of horses and cattle on the plains, goats in the hills, deer in the forests. From the savannah in the south upright apes, brute cunning in their eyes, mastering the crudest tools, flint and fire, bone and wood.

Someone should probably keep an eye on them.

I put some beans on to cook, they take longer than rice.

We’d been left in a world half-built, and no instructions. Obviously we were going to build monstrous engines of destruction. What choice did we have? Not build apocalyptic constructs? Perhaps we were fortunate that the Creator had left behind such extraordinary ideas that it would take centuries of labour to fulfil them.

Perhaps that was the plan. Give us time to work out an alternative. Or no plan, the Creator making it up as they went along. Like the rest of us.

No throne for the Creator. No king for the goblins. The Governor couldn’t see it. Goblins don’t need a leader. They need someone to shake them out of their habits, to pull the goblin round pegs out the square holes the Creator had left. King, governor, noble, these are not the highest aspirations for a goblin. There are better things to be. Cat-burglar. Troublemaker. Sceptic.

Trickster.

I’d done what I could. Tomorrow I would move on. I lifted the farseer to the horizon just as the sun dipped below, outlining something there, like a blade raised to heaven. The Manufactory Of The Dusk. Jack moaned loudly as the sun vanished.

Time to see what mess the girls had got into.