Dancing Pestilence

Dancing Pestilence

Moved out to the north edge of the city, the house was too big—rooms vast and multitudinous, mother said it were to do with prices, and the area, how we got such a big place; neighbourhood prices were down from there being no buses out or in this far so you had to walk a miles east at least to get anywhere, further, and there were many barred up windows, knockless doors—it had too many rooms, our house, and I felt a prince in a pauper’s palace, a blonde-headed boy lost in a haystack. My room was almost empty other than the fetid mattress, there on arrival, dead, too; festering within it things I tried not to imagine when I felt them crawling beneath my aching bones—a hatred of the room my brother and sister shared, and the door they hid behind, and their excuse from schooling—as for I, each day I would musten, wake the birds outside, clean my teeth with my nails and a bar of soap; then drag myself arse-first down the stairs until I got to the bottom, to the next set of stairs, another bottom, my damp leather boots, eventually I would reach the front door, leave the castle of filth and walk the streets until I arrived at school.

The first day I got lost. The streets this far out, here on the edge of the city, lose their direction, meander where they see fit. It was bright, much of the time, overcast but bright, a dull shine, exquisite lack of life. I were lost that first day, but I learned to and quickly recognise the streams as they presented themselves, each horizon a breaking point like susceptible to pushing in the right way, you’d find it, you’d find your way; that part became easy enough, but muster might enuff to reflect the destination: school. If the outskirt streets were dense, the school’s corridors were packd like atoms and doubly arranged; the moment I made it through the front gates I took a proper serious breath but before I knew better I was lost again—this time in a maze of childish hallways. Flaces burred around me, tapped, cronfonted; I fell, I stood, I regained like what I had before, those moments of feeling the streets and pathways and walking where it went—but school did not live by those rules.

Instead, the corridors rattled like the tube—underground train network that connected much of the city—likewise daubed in like graffiti and slurs—faggot greeted me immediately and I heard the word echo, somewhere, down one of the other corridors, lined with doors, sailor’s peepholes upon them, the hallways crashed and rattled like a domed iron casket full of commuters down the tunnels beneath the city, a boxcar throe the Western night, packed of hay and forty-swigging crust; all this I had learned not in the walls of a prior school but with my own mind and eyes—and lessons alluded only to me, here, too.

The first lesson of this education prison became a blur within minutes. Others stared across the room, I was blinking—a stray eyelash had like embedded itself crudely into the duct and I prayed not to cry from the stress, trying not to gather attention. The teacher was bald, I remember that much. He wore a fine suit, striped, braces, white shirt and a strange lightning bolt tattoo like a tear on his upper cheek. I felt its tense wish for release. His eyes were so blue to be grey—shallow pits of gravel. His words relayed the correct ordering of numbers. I didn’t take much of it in.

To get to the lunch hall, first I had to get to the plaza; I asked another student how to reach the plaza, and they said something to the effect of, “through the science block,” and disappeared into the map of dye running, faces and stockings. I didn’t know where the science block was. Eventually, I found a teacher, in a distant classroom, or rather adjoining a classroom, a lab, perhaps!—“Is this the science block?”—“No, it isn’t. Are you new?”—“Yes, sir.”—“Have you been to the toilet recently?”—“No, sir.”—“Are you planning on going now, or soon?”—“No, sir.”—“Okay. Let me know when you do. I’d like to accompany you.”—I left in a hurry, graced that he had not asked my name, and if I kept fidgeting I would—but I didn’t know where the science block was. Before long, lunch was over, and I redirected to my next classroom, just throue a set of wooden doors, also with those peepholes at eye-height; at a distance, you could get a good view of someone’s arse, but it made me feel weird. Later I made a friend, Joseph. I asked him how I was supposed to get to the science block. He said through the maths block. How do I get there?—Through the English department.

By the end of the day I was fidgeting and fidgeting like terribly. I needed to piss. Little come-flecked peeks squirted when I could not hold. Little leaks down my leg. Stained white cotton. These strange shards of what, dried semen, or something, I knew not, dappled my urea. Joseph shouted after me why I was running so fast out of those doors. I told him I had to run home and piss—he lived nearby. Sometimes the light beat down like an eclipse out there, grey skies and a great black occluded sun, I couldn’t take my eyes away. Joseph took my hand and I found myself in his room, sucking his cock. We were young, but it was fine, we had seen it before. He sprayed it across my face. We were both circumcised, but he had lost his bris much later, experimenting with a fishing hook. I stroked the scar with my tongue, and realised I had pissed myself, all over Joseph’s bed. He pointed out the white and yellow flecks, like beached sea monkeys across the Darth Maul linen.

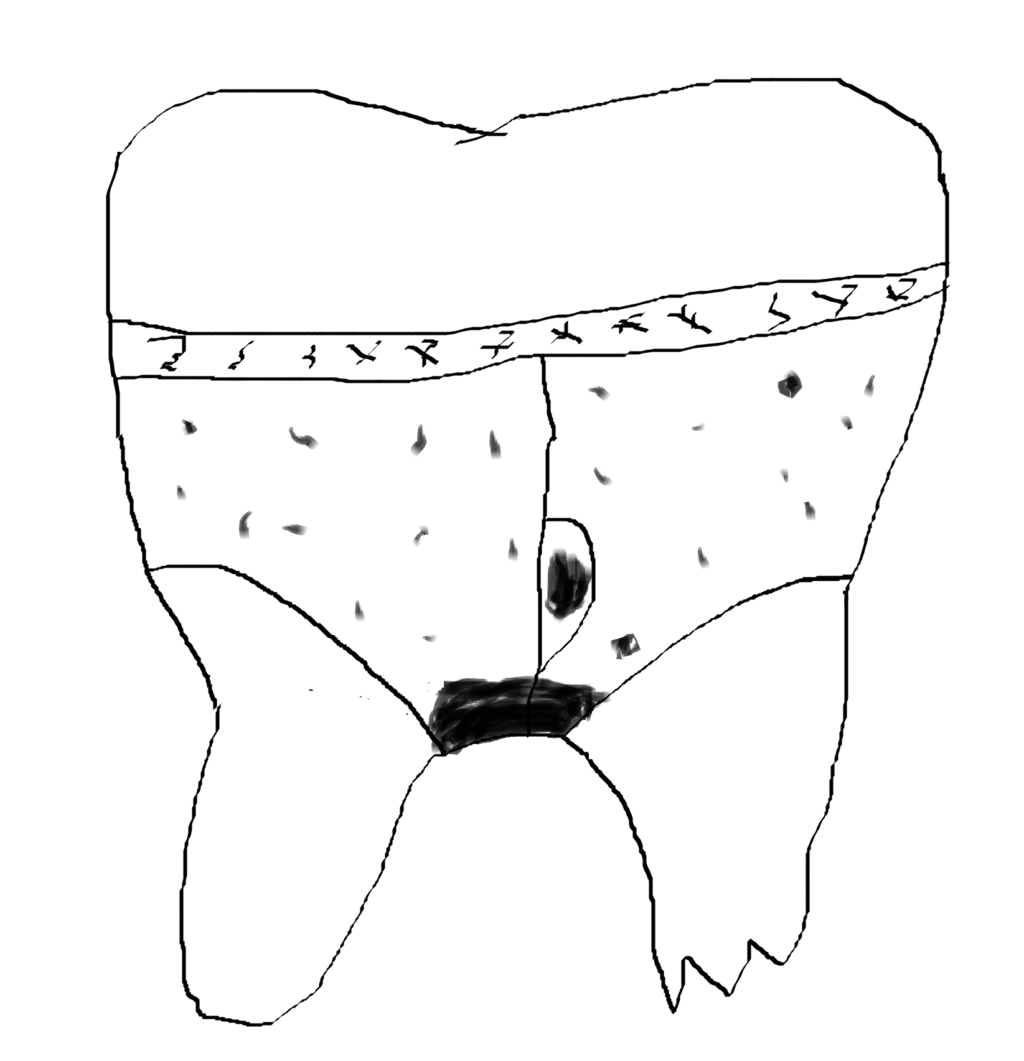

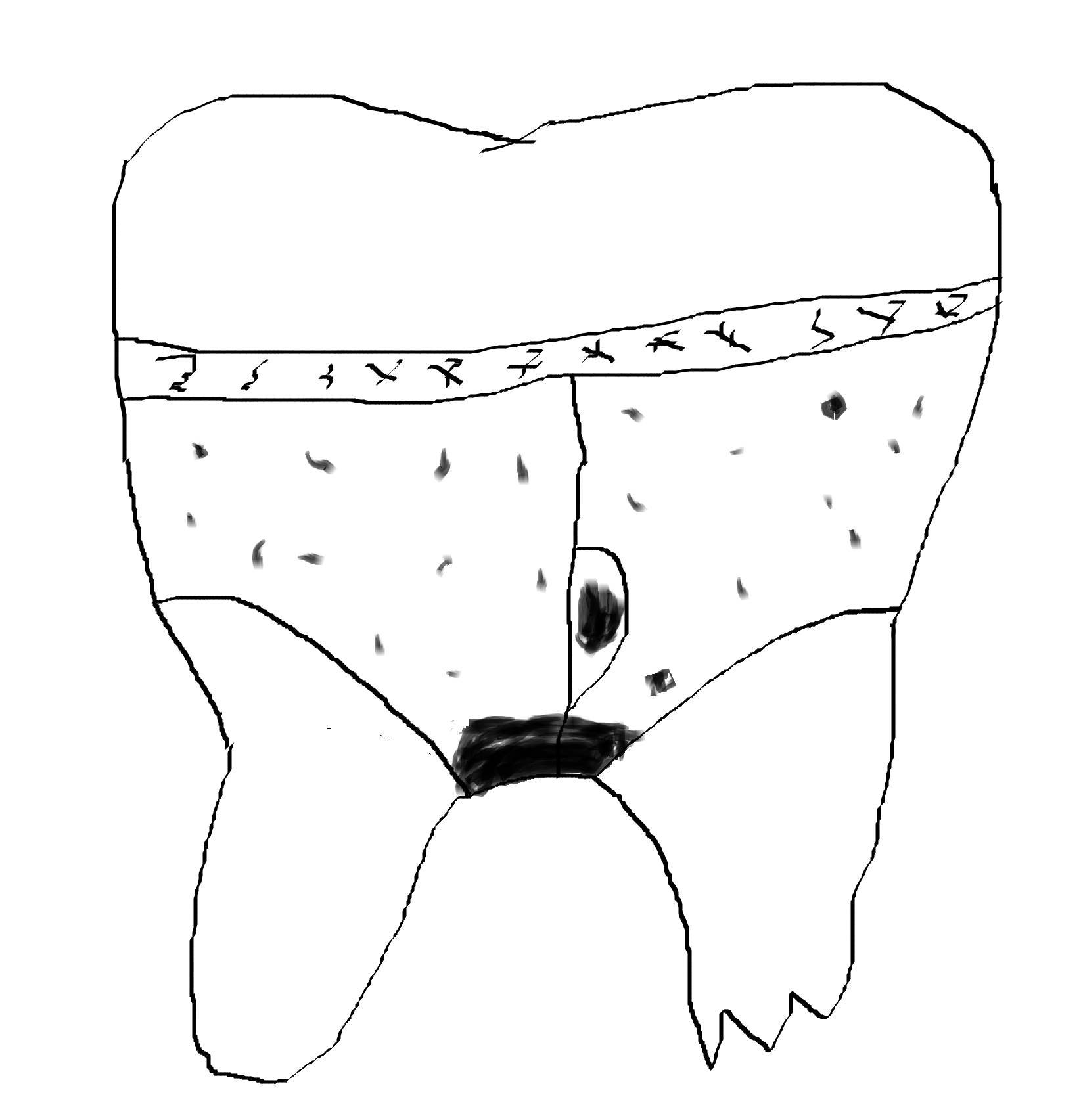

Asked him about that teacher, but he didn’t know him. Then, about the black sun. He said it just got dark around here. I said that wasn’t it, but he put a finger in my mouth rubbed squeaking—gasped, giggled, pissed myself again, but on purpose this time. Joseph called me disgusting, and that he loved me. He said anyone who pissed themselves twice on first fuck had to be special; I excused myself, and pointed out that we hadn’t fucked. He said that he guessed we would. I shook my head and frowned. What about next time? I nodded. Probably. He smiled. All right, sure. Want to see my arse hole? No, I said—not right now, anyway. Maybe later. I don’t usually do stuff like this. He said suddenly that I had to be careful going home because kids get all stabbed up in this part of town and found with their—he grimaced, like look it’s different when it’s in films and games and that but the kids around here our age are being stabbed up bad by some sick fuck and no one—well like—and Joseph was keeping his composure, he didn’t get angry—he cuts their cheeks open, right, and takes their teeth out, and then the next kid he kills, see—well like—he puts the last kid’s teeth in the next one, the next kid getting those replaced teeth, you see? He’s a dentist, I suppose. Some fucked surgeon or deranged doctor. Well he’s done done it a done it a few times and like it has been a few weeks—okay Joseph seemed a little angry there, but no fear in him—since the last one; so, be careful, when you go home. I kissed his knob and tried to smile.

Without Joseph it was a crawl getting home, but I was not accosted, the walk was pleasant despite the worthy anxiety, muster heartily all the courage I had, bent backwards, wishing stone sentinels would build a landscape in expediency like a better picture in my head of the whole scape, I wanted in particular to memorise a route to Joseph, from school and from home. At home, everything was still too big. Something about the scale of things made me feel sick, and I could hear brother and sister laughing and playing in their room, laughing without me, or at me. Mother was still at work; or commuting and then walking home from the centre of the city. She had a more miles than I to distance. All the better to sequester. My spoiled throne. If I pestered mother when she returned, if I begged indeed, she would let me have my own bed… even a bunk with brother and sister, and I could play with them. But I didn’t want that. I had what I wanted.

Coughed myself to sleep; damp as it was, my lungs splashed. Many nights like that first, all becomes too clear, always the path was open to me, I saw the paths, but in the outskirts—they were not suburbs, nor even sub-suburbs; rows of cracking exteriors left to reign in dirt-cacked disorder—could not see through them. The school I found with difficulty each time, a certain barrier would eventually open up and I’d be belting down the last few mishappen (oddly curved, overgrowing with weeds, piebald with potholes) streets, arms curving off like hooks in each direction, I’d find myself like bleeding at the knees caught on thiskle branch or whatever and splay kneed on the gravel path from falling over. There would be school, eventually, but how long it took—until Joseph started walking with me from my door. We didn’t share every lesson, but numerous. I wondered where he was when he wasn’t around. I resolved again to find the canteen, and on a second try I found my way—guided by Joseph. Distance seemed to disappear, be destroyed, die. The chips were stale, the pizza inedible. Otherwise, they had mashed turkey in breadcrumb dinosaurs, and packets of crisps. The only drinks were Diet Coke and Coke Zero. I brought my own lunch before long.

Couldn’t always rely on others to get me where I needed to go; a lot of the kids took the labyrinth aspect of their school at face value, and found ways around with ease, I would lag behind and be lost again, imaging paisley prostrations upon the paving—not paving, carpet, and vertically across the walls. I could lose myself in those patterns for minutes at a time, rarely getting anywhere I needed other than my classrooms. One day without Joseph I found a set of double doors, of course with the spy holes, peepholes upon them, more like a glass dish; larger sections of glass below, could see ppl’s underwear at that angle as they walked up the high stairs—it appeared unlike the rest of the school, a more modern look, but unfinished; I went throe, to find out if their facilities were easier to access, but as I approached the door a voice whispered, “we heard Mr Matthews likes you,” and on they went, and I was shaking from certainly the cold as I made my way through to that larger intersection, lots of pairs of underwear on display but they were children younger than I and it made me uncomfortable, and holding in the piss, a little dribbled out from holding it so, so hard—I asked a teacher where the nearest toilet was, I think it was a teacher, who said, “Oi,” and pushed me in the chest when I got too close or something, then pointed up the stairs, “up at the top,” and walked off. All the way up those stairs, and at times the banisters seemed perilously low—students in this location were rowdy, a shoving lot, daring each other to get close to the edge or shocking the shoulders of classmates and making them think they were gonna like fall. I managed the last few flights and looked down at the little figures scurrying below. The place was huge all the way to the glass ceiling, and above burned down the black sun. Also it was mostly empty at this level, although students levels below stared at me as if I were trespassing—the classrooms around were empty, mostly without desks or chairs, electrics gutted and windows boarded up. Found the toilet though and went inside. At last; I was ready to not only piss myself but shit myself, too. Shitting at school was the worst thing I could imagine, but this area was quiet. Maybe it would be empty.

It was not empty. In fact, there were eight other students—I thought they were all students at first—who had made this restroom their… I didn’t know what to call it. Of the three stalls, two were taken, one of the doors was open: I saw there two boys, each stabbing the point of a pair of compasses into one of the kids knees, and nutsack. If I had seen it in a film I might have vomited, but it was very real in reality—very, very red, and white, which I think was bone or something, muscle, some purple on the ragged ball bag, so real was it all and so red that I had nothing to puke for it, only one destination, my destined bowl; from behind the other, middle, stall, closed door, a horrid squelching burp, sloshing, a pair of legs akneel upon the floor, evidently puking its guts raw, from the brown beer bottles that littered the porcelain. I caught sight of something roughly sketched and gyrating vile in the corner by the urinals, my mind erased it—somehow, for it was substantial—and then like I was on the shitter shitting, a bad spot of meat had given my bowels a running, it was wet, and also red, but not from blood. There was no toilet roll. I started to shake. Then I remembered what I had seen: five others, one was a girl probably only around twelve, or younger—or older—and she was drooping around held by the shoulders I guess with white powder around her nose and I heard then in the remembrance, “give her some more sherbet,” they were sniffing it, too, the girl did not make a sound and could have been dead for all I knew, I was shaking and shitting at once as I tuned into the stabbing rink two down the vomit hole one across and to my end the rape of an unconscious child, in the bathroom, at school—most of her uniform had been removed and scattered, some draped in the urinals, her skirt remained, hidden was the most of the sight of it I thanked, but I had seen her limp face, eyes barely open, breasts barely grown, going back and forth with white on her nostrils, four boys fucking her against the tiles, and I felt like the one next to me but instead I excreted my grief and focused on… no toilet roll. Another had taken over on the girl now, it sounded like. The boys were all brown-haired, two of them not much older than the girl, one had been taller… a voice came throe, well like it was all around, “you’re Mr Matthews’ new favourite lad, aren’t you? He’s been looking for you. Chuckles is off to let him know you’ve done a shit unsupervised,” I was done shitting, I said, I was done, if they would pass me some toilet roll and I could leave, I shouted, there was laughing and then another sound—gurgling—the girl—awful little moans, no, groans, and the voice said, “I’m sure Mr Matthews will clean your little arse up, faggot,” and I banged on the stall next to mine and I will admit here I was crying for I knew not what to do or whether it was all a horrid, horrid dream—it was not, unless each waking day is, which it is not, for I have since studied the nightside in effort.

Pulled my pants up and let my shitty arse and legs be shitty and ran out of the loo without looking again at any of it, or hearing another grim sound. A last part of the memory came to me: that the two other boys had been taller, with stubble on their faces, whiskey stench around that whole place not covered by the dung, and althoem they were wearing uniforms, it was—they were tights, borrowed, stolen, or simply taken—both had not been boys but men in their (I guessed at the time) thirties or forties (but upon reflection I believe twenties to mid-thirties) that had been taking the poor girl the hardest and pouring drink on the younger boys. The images remained in mind as I thought of Mr Matthews, some guy, that guy—why had ppl been speaking about me with him?—in that dark lab, or it wasn’t a lab, and the shit in my pants and that on my legs that Joseph cleaned off in his bathroom after school as I sobbed.

Penis fired into my anal cavity. My penis. The angle Joseph had got me at cleaning away the poo, we’d been able to angle my junk so it was hard enough and flexible enough to enter my own sparkly clean arse hole. I let him bite my girl-like nipples in the bath, but focused on myself to finish, like usual, althoue I had never stuck my own thing in there before, mostly conceptual things, but Joseph had opened that door, I guess. I still do it now; once you know the angle, it slides in every time. He knew he wasn’t getting a go on me that time, either. We had not fucked, only done things to each other, often things like that, we didn’t mix shit and play but we did a lot of piss, and I guess if I had to put an age on it, then thirteen, or fourteen, which seems normal to me, now, somehow. Time dilates with your anus and things only get more and more lost in there. I told him about the girl I saw, and all the stuff with—don’t think about it, he said, Joseph said, stroking my shoulder. They can’t get you if you don’t let them. There were never anybody about on the streets where Joseph lived. A dead town, ghost town. He spoke about the new kids cut up on the block; someone found a stabbed baby, the youngest victim yet, in a bin, fresh from the maternity ward; there were no teeth related to the crime, so there was debate whether it was the same killer. Joseph said it was. Two other boys had been added to the sequence, those brown n velloe chompers crossed with the poor kid before and the latest set missing. The baby had simply been stabbed; the delicacy of the game of teeth was far too precise for a such a self-debasing rugger slayer. I didn’t mention this to Joseph. He called me messy, but in a cute way, and stroked my hair, which had grown out to my shoulders. I wasn’t a girlfriend and I wasn’t a boyfriend. Joseph walked me home. I invited him in, then balked and said my mother was a cunt, and shut the door after another kiss; then I went to bed. Up the stairs, all was quiet in brother and sister’s room. Mother asleep. She was not a cunt, but I resented her not giving me the same as the favoured two—and she had known moving out here it would be I doing the great walking out of the living chidren, and certainly more than Daddy-popped-clogs! As for her, she took the longest route through the hardest terrain and cried at the results found upon blistered feet, cracked and swollen toes.

Looked up the killings on the internet and found stuff about the area and like how a mile away like ten years ago they found the remains a fifteen year old boy burned as a scarecrow—no arrests—and like five years ago the whole district goes to shit and the roads are too damaged for bus drivers to handle so they quit the routes until they are fixed and by God they never, ever are; even now, these years later, I hear of that part of the city, how there are deeper holes than ever where one might take a stumble too far under no street lamp or else flickering antibeacon of lumpen clavity and never find themselves again. There had always been killings; then, that goes for everywhere, look up any home town and I will show you a crimson Potemkin settlement so like the last to the degree of temporal actuality, cherished in a history of abuse. But I looked hard enough and made myself feel sick enough that I eventually came across a story of how young boys had been butchered and had their teeth removed, all at once, not far nearby and all that you know, from my house, and then from Joseph’s, and it looked as if lotta the victims were—Perchance! All from the same school; my school; and it had been going on three years. Not a word of this when we were gathered in the redwood shone shining wood panels for assembly, yet the pieces had puzzled themselves solved automatically. And that girl was still being raped in my mind—I could barely sleep that night. Mosquito on my arm—an early reckoning. How long had he truly been swapping teeth? Their underwears were always stained in cacka, which is what the form does at the point it decides to die, goes all-out; but they said the shitted pants and pissed shorts were earlier than the death—so the kid pisses and shits, and then he stabs the kid to death, and then does the teeth surgery, then drops the body off somewhere to be found.

There’s these like arse holes in our area basically called the Kerkers and they’re like if racist skinheads were crossed with other, more aggressive racist skinheads, I don’t want to give them much time, anyway one time when Joseph walked me back the black sun belt down and pulled us up by its boot straps and cast us in the path of fourteen Kerkers, and no myth, they saw us as faggots and went in. They were like forty (twenty) years old. We got our shit kicked in and out but they left us alive and we crawled bleeding and blue back to Joseph’s room and I let him do me really hard in my arse with his cock. The first time it had been done that way by another kid, and the first time I got come up there that wasn’t my own or that of someone related to me. It felt really, really good, and I guess at that point we were in love.

Mother had been talking about getting new beds for brother and sister. A pointed silence. A place for me to make my beliefs known. I sucked my thumb like a defiant toddler, wore boots inside to make as much noise as possible; much like the sound of his feet outside, in the last house, smaller, contained, you think I’d like the extra room—clogs popped and I had considered a pair of those too bc that would really make ppl hear. The mattress stunk of the mushrooms that walked within. The house proved no further surprises however, and before a half of a year I knew eery inches: the stair to the top, an attic at that, which was crammed with dream-treasures—reality-trash—before long, really, it all seemed too small; or, would seem that way, if I were there when it could be helped, which I was not, and instead slept beside Joseph, whose junk-addicted parents farted themselves into the couch to quality quiz programming whilst we traded penetrations, and withheld them, and moved beyond them, and held each other, and he gripped an arm around easy as I sighed or whatever. There was a lot of ejaculation followed by weeks, then months of soft gazing and sighing. Regardless, we spoke. I couldn’t tell you like the words in every place, only in a few, and even then, ones frequently devoid of declarations of love, just stuff about who was the gayest and whether the Kerkers were gonna kick our arses again or about the killer who continued upsetting naive grins.

Around this time I started thinking I was Hitler. I found myself in the sky, watching over my subjects, awaiting return—a cleanse of the land, not of Jews or queers or commies but… I wasn’t sure. It never seemed broad enough for my hatred. Hitler was queer too… neurodivergent… I never learned a damn thing about the Nazi party but it found its way into my head, and I had to be the God of it. I don’t know why I add this detail, it’s not relevant to the events, but it seemed worthy to note. You can have all kinds of crazy beliefs as a kid, crazy experiences. I would come to chanting eight, eight, eight, nightly, Joseph would muffle my mouth with a pillow and ask if he was Eva Braun. He clawed my back until it bled. School stank of hydrogen cyanide, could hear that girl’s defeated grunts around the clamour all times…

There was a science lesson. I sat at the front, trying to steal personal possessions from the teacher’s desk. I had succeeded several times, and argued with the teacher long enough to avoid detentions—I simply denied everything. Mr Matthews came in. I knew it was him—I had seen him around since, he watched me in the corridors, he walked behind me, he whispered, and other students said I was his favourite, when I’d never spoken to him again since that first day. He was an ordinary man in his forties, brown hair, a full face, brown moustache, a slightly gap-toothed smile as he began the experiment—he was not a proper teacher at all, an assistant who operated bunsen burners, and dissected frogs’ livers; he exampled to us that day the inside of a pig’s eyeball, and we were to have our own go. The class scuttled to lab positions but I already had my place, there with Mr Matthews. His stench was unbearable—rotten, clotted milk, rancid saline sweat, as if he did not clean out of protest—an odour that denied others their right to clean air, that demanded your offense—and it billowed out of his shirt as he sidled up behind me—“I’m your partner today.”—“Right, sir.”—“Are you clean?”—“No.”—“Why not?”—“Because I’m not.”—“I should clean you. Do you want me to clean you?”—“No.”—“I’m going to clean you.”—“No. No, you’re not.”—I pushed back and stormed out of the class, out of the school—a direct path, I forged—somehow Joseph noticed, caught my escape from an upper window—he found me smoking stolen cigarettes by the dry canal, puking, shaking. He held me.

A lone Kerker appeared, calling us faggots, said he was going to get his mates. Maybe he wasn’t a Kerker, some other violent piece of shit, but Joseph wasn’t taking chances: he ran at the dude and like grabbed him and dragged the bitch to the edge of the canal and like just hurled him by the collar into the waterway and heard like as the guy went in at a funny direction and yelped or welped and landed on this terrible angle and his neck just went crunch, it’s a snap sound, a snapped neck, something I’d never heard before; Joseph was freaking out and crying and apologising to me for some reason and I was just laughing. I thought it was the best fucking thing. The guy was just a lump down there, pale skin and dark leather sizzling under the black sun. Joseph was calmer, swearing under his breath, saying like fuckfuckfuckfuckfuck and I said listen you did it good and that snap sound was legendary. He was just some scum and now he’s dead scum. Who cares if someone will miss him. They can fucking die, too. They can all die. Let’s take them down here and throw them in this here canal dry dock thing and cover them in petrol and set them alight, get a real smell going, riddle them with machine gun fire. I spat on the man’s spastic corpse. Joseph took me home and gave me a good fuck—one of our best. He made me fish fingers and spicy chicken strips, we shared, we kissed and watched—I can’t remember. Some film with Alain Delon. There was this weird bit at the end where it was just static shots of the day passing. Everything got darker and darker.

Excluded from school for my behaviour and mother was fucking like “WELL YOU ARE STAYING IN YOUR ROOM AND THINKING ABOUT WHAT YOU HAVE DONE!!”—I couldn’t even see Joseph, she cut off the internet, she took my fucking phone, and other than threatening suicide there was nothing I could do, and doign that would like fucking just have made it hardter and so instead I wrote a manifesto declarinf my intentions from then on; I kept Joseph in mind and composed it, it read: My struggle… [EXCISED] I was allowed my phone back after a point and I tried msging Joseph but got no reply. I tried calling. I msged. I called. I phoned. I spent days scratching the walls. I begged for the internet, I begged for for it, I said PLEASE but no avail no avail, I ran out of credit to call and just txtd saying like please Joseph i havent left u i havent gone anywhere im still here pls msg back i love you pls msg me i miss you so much so much pls pls like im so grounded and it sucks and i love you pls get back to me i adore u and i want u and u should come here and get me oytu of here i hate this shit hole lets just go back to the city and slum it idk like anything, anything you know pls msg me back Josepg im adore you SO much pls pls pls—et cetera for days—and crying to mother please PLEASE no avail no avail just crawling there within and without my skin and wondering wondering, it hurt worse than anything else, a gulf of acrid distance, sizzling skin… I wished I could watch him kill another scumbag… righteous boy, my boy, I needed him, I thought about what his form was like but it was lost to me, his face was lost to me, anything beyond the prison cell of my room was lost to me… brother and sister were laughing at me… mother was absent… father was killed… there was nothing real left but I. Alive, dead: a ball of genocide, a divine suicide, teenage assassin, castrated saint.

Walked alone to school on the Monday back and like as u can probably guess I got lost, this time for real, Joseph had walked me so many times that I had not sharpened my own route, so I traced the pathways of my mind until they carried me to a door that I recognised as Joseph’s. There was no knock, no answer, just a hollow thing where sound should have been. I walked on. A rubbish truck went fucking beeping past, belching black sacs from its metal anus, trash strewn across the pavement, the walls, I watched it crash into a pedestrian, some old guy, and it just kept going—the man was incredibly dead, coated in his own blood and the remnants of used nappies. I stepped quickly over the sludge and refuse and in fleeing the stench so vile I traded one for another, for the sharp evil of Mr Matthews struck my nose… and it led me to the school… I was given a detention for being late by the lady at the front gate which I took without argument… she told me to go up to the assembly… who else was leading but Mr Matthews. His stench superior, overpowering, a trumpet blare as I open the doors to sudden silence, all eyes upon me, the whole school, and Mr Matthews says—“You’re here at last.”—I say nothing and take a seat at the back.—“Today is a special, and very sad, assembly.”—My gut clenched. I had not been to the toilet before I left. The bacon, I recalled, was out of date, but I had eaten it anyway. The eggs, too, had been somewhat smelly. I needed to shit, but was stuck to the seat, for if I stood again all attention was on me… I wanted to, but… what difference?—“A sad day indeed as we mourn the passing of one of our students, Joseph Atticus, who was,”—it was as if I already knew—“brutally murdered last week. Here are some photos of his corpse.”

They were displayed on the projector—Polaroids, first hand evidence—and I closed my eyes and did not open them again until they were gone. I had seen enough, though; and could not block them out. I had seen the bindings on the wrist, stab wounds, dozens of them, and the close-up of his face, the teeth blackened, full of fillings. Not his teeth, not his own fine teeth… I shat myself. Consciously, I let it go; it was a glorious feeling, to submit to raw physicality and shit myself, to exclaim apologies and hurtle from the hall, trailing liquid excrement behind me. Those hideous teeth in that beautiful face… I puked through tears, covering a wall with my insubstantial bile, a young teaching assistant exclaiming and running, calling for help. I did not need help. I traced the hallways as Joseph had taught me, I traversed the maze and found that strange room, that darkened lair, the crypt of an insane lab assistant, a rogue disgruntled dentist, whatever he truly was; within a locked cabinet that I struck my way into, somehow, in that state of absolute direction—within, within, a little glass case, a little arrangement, teeth, pure, clean, white, better to be set in the face I missed, marked #53 Joseph Atticus, arranged for the next boy, and the next… and I took them, and kissed one, and hid them in my pocket. When I tell the story here I usually want to embellish and say that Mr Matthews came in to confront me, or that he followed me through the school, chasing my trail of shit, calling out to clean me… but he did not, instead I left with Joseph’s teeth, I did not look back, I walked one great long road to that house that then seemed so small, so tight, so empty, and without saying goodbye to brother, sister or mother I left for good, and with the black sun to my back I walked south, and I kept walking until the sweat ran down my aching, growing chest, until the streets at last made sense.

I’m nearly, impossibly, speechless. I’ll go with the ordinary and say ‘brilliant’, though that’s not the right word: those right words are right here, and nor am I done talking about this. Challenge yourself here: can you dance all the way to the bottom?